Conceptualisations of peace, its benefits, and strategies related to political orientation among Colombians

Conceptualizaciones de paz, sus beneficios y estrategias relacionadas con la orientación política entre los colombianos

Conceptualizações da paz, seus benefícios e estratégias relacionadas com a orientação política entre os colombianos

Claudia Pineda-Marína,*| Diego Alfonso Murciab | Laura Camargo Martínezc | José López Martínezd | Nicolás Mendoza Medinae | Quena Peñaf | María Trujillo Santiagog | Laura Taylorh

a. https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0952-6522 Fundación Universitaria Konrad Lorenz, Bogotá D.C., Colombia

b. https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5741-4317 Fundación Universitaria Konrad Lorenz, Bogotá D.C., Colombia

c. https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9254-3293 Fundación Universitaria Konrad Lorenz, Bogotá D.C., Colombia

d. https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3672-8856 Fundación Universitaria Konrad Lorenz, Bogotá D.C., Colombia

e. https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9456-0401 Fundación Universitaria Konrad Lorenz, Bogotá D.C., Colombia

f. https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4364-6517 Fundación Universitaria Konrad Lorenz, Bogotá D.C., Colombia

g. https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9572-2609 Fundación Universitaria Konrad Lorenz, Bogotá D.C., Colombia

h. https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2353-2398 University College Dublin, Dublin, Ireland & Queen’s University Belfast, Belfast, Northern Ireland.

*Autor de correspondencia. Correo electrónico: clipineda20@gmail.com

- Fecha de recepción: 2024-09-05

- Fecha concepto de evaluación: 2024-09-30

- Fecha de aprobación: 2024-10-18

Para citar este artículo/To reference this article/Para citar este artigo: Pineda-Marín, C., Alfonso Murcia, D., Camargo Martínez, L., López Martínez, J., Mendoza Medina, N., Peña, Q., Trujillo Santiago, M., Taylor, L. (2024). Conceptualisations of peace, its benefits, and strategies related to political orientation among Colombians. Revista Logos Ciencia & Tecnología, 16(3), 11-29. https://doi.org/10.22335/rlct.v16i3.1987

Abstract

Political orientation has been shown to affect the opinions of ordinary people when it comes to socio-political issues. In Colombia, 74% of citizens indicated that they did not identify with any political party; however, opinions against and in favour of peace and its processes are characterised by a dynamic of constant tension among citizens, similar to that among the country’s political parties: left, right, and centre. The purpose of the present study was to identify conceptualisations about peace, its benefits, and the strategies to achieve it after the peace agreement signed in 2016 between the government and the FARC guerrilla based on the political orientation reported by the participants. Textual data were analysed using KH-Coder software to identify co-occurrence networks of peace conceptualisations, benefits, and strategies. A total of 346 men and women participated in the study. Results show differences among the conceptualisations of peace and the peacebuilding process among supporters of each political orientation, including apolitical participants, although right-wing participants were the most differentiated. Results are discussed.

Keywords: Peace, peace construction, obstacles to peace, peace process.

Resumen

Se ha demostrado que la orientación política afecta a las opiniones de los ciudadanos de a pie en cuestiones sociopolíticas. En Colombia, el 74 % de los ciudadanos indicó no identificarse con ningún partido político; sin embargo, las opiniones en contra y a favor de la paz y sus procesos se caracterizan por una dinámica de tensión constante entre los ciudadanos, similar a la que existe entre los partidos políticos del país: izquierda, derecha y centro. El propósito del presente estudio fue identificar las conceptualizaciones sobre la paz, sus beneficios y las estrategias para alcanzarla después del acuerdo de paz firmado en 2016 entre el Gobierno y la guerrilla de las FARC, en función de la orientación política reportada por los participantes. Los datos textuales se analizaron utilizando el software KH-Coder para identificar redes de coocurrencia de conceptualizaciones, beneficios y estrategias de paz. En el estudio participaron un total de 346 hombres y mujeres. Los resultados muestran diferencias entre las conceptualizaciones de la paz y el proceso de consolidación de la paz entre los partidarios de cada orientación política, incluidos los participantes apolíticos, aunque los participantes de derechas fueron los más diferenciados. Se discuten los resultados.

Palabras clave: paz, construcción de paz, obstáculos para la paz, proceso de paz.

Resumo

Foi demonstrado que a orientação política afeta as opiniões das pessoas comuns quando se trata de questões sociopolíticas. Na Colômbia, 74% cidadãos indicaram que não se identificam com nenhum partido político; no entanto, as opiniões contra e a favor da paz e seus processos são caracterizadas por uma dinâmica de tensão constante entre os cidadãos, semelhante à existente entre os partidos políticos do país: esquerda, direita e centro. O objetivo do presente estudo foi identificar as conceitualizações sobre a paz, seus benefícios e as estratégias para alcançá-la após o acordo de paz assinado em 2016 entre o governo e a guerrilha das FARC [Forças Armadas Revolucionárias da Colômbia] com base na orientação política relatada pelos participantes. Os dados textuais foram analisados usando o software KH-Coder para identificar redes de coocorrência de conceitualizações, benefícios e estratégias de paz. Um total de 346 homens e mulheres participaram do estudo. Os resultados mostram diferenças entre as conceitualizações de paz e o processo de construção da paz entre os partidários de cada orientação política, incluindo participantes apolíticos, embora os participantes de direita tenham sido os mais diferenciados. Os resultados são discutidos.

Palavras-chave: paz, construção da paz, obstáculos à paz, processo de paz

Introduction

Ordinary citizens’ opinions are strongly permeated by the discourse of their political leaders. Just as political orientation (whether right- or left-wing) can have an effect on people’s attitudes toward issues such as regularising drugs, the right to abortion, and euthanasia, it can refer to neuralgic issues such as the everyday discourse about transitional justice processes (Observatorio de la Democracia, 2019). Even though 74% of people in Colombia declared that they had no political orientation in 2018 (Observatorio de la Democracia, 2019), it is important to know whether their opinions are different from those who claim to be sympathisers of political parties of a given orientation. Therefore, this study sought to compare conceptualisations of ordinary people about peace, the benefits of peace, and the strategies and obstacles in building it. We also studied people’s beliefs about statements circulating in traditional media and social networks regarding the peace process in Colombia among people who are said to sympathise with right-wing, left-wing, or centrally oriented political parties and among those who are said not to sympathise with any political party.

The definition of peace and the strategies to build and negotiate peace are, in general, a contested scenario in which the perspectives of ordinary citizens are key to the construction of bottom-up peace, that is, from the personal to the social sphere (López- López, 2020; Taylor et al., 2016). The first studies on peace date from the end of World War I and the beginning of World War II (Kriesberg, 1997; Miall et al., 2005; Valencia et al., 2012). Studies focused on negotiated conflict resolution emerged after World War II (Harty & Modell, 1991; Hato de Vera, 2016; Kriesberg, 1997). At least two lines of peace studies have been defined: on the one hand, a so-called minimalist current, and on the other hand, an intermediate one (Galtung, 1969; Hato de Vera, 2016; Kriesberg, 1997;

Miall et al., 2005; Ricardi, 1967; Touzard, 1981). Subsequently, another current referred to as maximalist considered not only international and national violence, but also real violence, virtual violence, direct violence, and indirect violence (Azard & Burton, 1986; Curle, 1986). Contemporary peace studies include gender, cultural, ethnic, religious, and economic issues, and they use definitions closer to positive peace or even to imperfect peace or multidimensional peace (Barash, 2000; Fisas, 2010; Galtung, 1969; Hato de Vera, 2016; López-López, 2020; Rettberg, 2003; Valencia et al., 2012).

Another research line focused on the meanings of members of civil society about peace in Colombia, for instance, those of social leaders (Alcaide, 2015), communities committed to civil resistance as a mechanism for peace (Hernández, 2009a), indigenous people of African descent and agricultural workers (Hernández, 2009b), young people living in sectors where the armed conflict was intense (Tovar & Sacipa, 2011), people living in rural and urban areas (Socha et al., 2016), and before the demobilisation of paramilitary forces (Taylor, 2015; Taylor, 2016a; Taylor et al. 2016), university students (García-Vergara & Carillo-Lizarazo, 2017; Giraldo-Pineda et al., 2018), and young people directly affected by the armed conflict (Pérez et al., 2020) However, conceptualisations of peace as a function of political orientation have scarcely been covered by academic research.

The context of the Colombian

conflict and the peace agreements signed in 2016

The Colombian conflict had its roots in the 1930s when struggles among farmers arose amidst unjust land distribution and a lack of agrarian reform. However, it was not until 1964 that the dispute was formalised, when the state initiated military action in a series of municipalities stirred by Marxist ideals and the abandonment and neglect of the government; the “Marquetalia Operation” was launched, marking the formal onset of the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) (Pizarro & Valencia, 2009, cited in Ríos, 2017). Since then, the conflict has increased in complexity following the appearance of other armed groups motivated by ideologies such as Marxism-Leninism, Liberation Theology, and Maoism, as well as the emergence of paramilitary groups initially seeking to confront the guerrillas but later becoming criminal organisations pushing for territorial and political objectives. Over the years, the ideals of the revolutionary guerrillas faded into a series of groups that were closely associated with vandalism and drug trafficking (Ávila, 2020; Duncan, 2015; Giraldo-Ramírez, 2015; Palacios, 2012; Pizarro, 2018, Restrepo & Aponte, 2009; Restrepo & Bagley, 2011; Restrepo & Bagley-Villamizar, 2017; Reyes-Posada, 2009, 2016; Ríos, 2017; Ugarritza & Pabon-Ayala, 2018; Vargas-Velásquez, 2010; Zelik, 2015).

Colombia has a long history of more or less failed attempts to manage peace. Some of these processes took place in 1984, when the M19 guerrillas buried the hatchet and became a political actor, or in the failed attempt to negotiate peace with the FARC in 2002 and the demobilisation of paramilitary forces within the framework of the 2006 Justice and Peace law. But it was not until 2012 that former President Juan Manuel Santos initiated a formal peace negotiation process with the FARC, the oldest, largest, and most organised guerrilla group in Latin America. This process sought not to repeat the errors of other peace processes and to concretise the Havana Dialogues (Turriago-Rojas, 2016).

In 2016, in order to legitimise such agreements, a plebiscite was held in which Colombians decided on their endorsement. Surprisingly, after a campaign led by the right-wing Centro Democrático party, voters were not in favour of the peace agreements (Melendez et al., 2018). With 50% of valid votes against the agreements, Colombians rejected them by plebiscite by an advantage of only 0.43%. Various analyses were carried out to explain this controversial decision. Some of these analyses addressed issues such as the 62% abstentionism, urban-rural differences in opinion concerning the agreements, and the successes and failures of supporters and detractors in their respective campaigns carried out in the weeks prior to October 2, 2016. These circumstances partly reflect the intersection of the structural and political realms, which allows for a complex understanding of the plebiscite process (Botero, 2017).

In retrospect, one of the factors that could explain why the agreements were not supported by the plebiscite can be explained by the “No” campaign, through which voters were strategically and emotionally manipulated by the agreement’s detractors, turning the plebiscite into a referendum on President Santos’s administration and linking it with key issues for the conservative right, such as the supposed relationship between the process and the transformation of Colombia into a second Venezuela, indignation at the perception of injustice derived from the agreement, and the reasoning that the agreement broke the traditional concept of family. In spite of this, the Havana Peace Agreement was finally signed by FARC and government representatives but the peacebuilding process has been under constant criticism, highlighting the complexity and necessity of civil society’s participation in the commitment to maintain peace (Basset, 2018; Observatorio de la Democracia, 2019).

Dávalos et al., (2018) observed that sympathy with the political party that opposed

the agreements defined people’s stances on the agreement; they also pointed out that the Centro Democrático party managed to divert attention from the possible benefits of peace by relating the agreements with socially sensitive issues, that is, involving the transformation of social order via actions such as gender equality and the recognition of homosexual rights. Additionally, the Centro Democrático party framed the debate on the economic measures of transitional justice by defining them as rewards for crimes instead of highlighting the incentives of relinquishing armed insurrection (Caicedo-Atehortúa, 2016). Data from the Observatorio de la Democracia (2019) coincide with observations by Dávalos et al. (2018) in indicating that, to some extent, political orientation would explain stances toward the Havana peace agreements. For instance, this organisation observed that Colombians who sympathised with the Democratic Pole (a left-wing party) also agreed with the option of supporting the participation of ex-combatants in politics.

Peace processes around the world

and civil society participation

Several strategies in pursuit of peace have been implemented in countries such as Lebanon, Rwanda, South Africa, Togo, Ireland, former Yugoslavia, Israel, and Palestine, among

others. Civil society organisations have played a significant role in each of these processes. There are two main categories to this role: 1) the first is structural, and it organises public interests and helps to form and strengthen state structures that promote social participation; the second is political-cultural, associated with the dissemination of the behaviours and democratic values learned by individuals in order to protect and restore the political structures of the state (Kew & John, 2008). Some peace dialogues in Latin American countries illustrate the importance of civil society participation. These are the cases of El Salvador (Moreno, 2017) and Guatemala (Brett, 2017).

Context of the present study

In the Colombian peace process, opinions aimed at highlighting its negative aspects are still being disseminated (similar to the No campaign), which was reflected by a recent Gallup Poll survey from 2020 showing that 76% of Colombians believe that the implementation of agreements with the FARC was on the wrong track, whereas only 19% perceive the opposite. On the other hand, respondents were asked whether they believed that the agreements were being honoured; only 27% believed so, as opposed to 69% who believed the opposite. The survey also asked participants whether they were in favour of the continuation of the agreements; 66% indicated their support for continued dialogue until peace was achieved, in contrast with 28% of participants who believed that military strategy was a better option than dialogue (Invamer Investigación y Asesoría del Mercado SAS, 2020).

On the other hand, studies carried out in

Colombia (Cortés et al., 2016; Fergusson et al., 2018; López et al., 2018; López-López et al., 2013) have observed that ordinary citizens are willing to have regular everyday interactions with ex-combatants from the FARC and other demobilised groups (Dugand et al., 2018;

Taylor, 2015) and establish communication with people who have hurt other people, to share accounts of the violence with them, to volunteer, and to organise activities in the municipalities (Barómetro de la Reconciliación, 2019). However, in studies by Fergusson et al. (2018), some participants, depending on whether they were victims or not, were more resistant to reconciliation; similarly, in the approval of the current peace process in Colombia, differences were observed between urban and rural populations (Dugand et al., 2018; Rettberg & Ugarriza, 2016).

Method

Participants

The study included 346 Colombians (155 men and 195 women) from different regions (urban and rural) in Colombia. Participants were between 18 and 65 years of age (M = 32.62 years, SD = 12.66). Twenty-five percent of the sample had a low academic level, 15% had an average academic level, and 59% had a high academic level. Twenty-four percent had a low socioeconomic level, 67% had a medium socioeconomic level, and 9% had a high socioeconomic level. Fourteen percent of participants indicated that they sympathised with right-wing parties, 29% were sympathetic to centre-right parties, and 20% were sympathetic to left-wing parties, whereas 37% of the sample had no preference for any political party. Intentional non-probabilistic sampling was carried out. Participation was voluntary, and the only criterion to participate was being an adult (18 years of age, according to Colombian legislation).

Instruments

Six open-ended short-answer questions were designed. The questions asked were: (a) how do you define peace? (b) what do you think are the greatest benefits of achieving peace according to the way in which you defined it? (c) what would be the strategies to achieve peace as you defined it? (d) what are the biggest obstacles to achieving that peace? (e) please describe three positive aspects of the Colombian peace process, and (f) please describe three negative aspects of the Colombian peace process.

The five questions were constructed as affirmations aimed at evaluating the level of veracity held by some of the postulates inspired by the “No” propaganda campaign regarding the endorsement of the peace agreements signed between the FARC-EP and the Colombian government in 2016 (see Appendix A). We used an Osgood scale from 0 to 10, with two anchors ranging from not true at all to completely true.

Procedure

To collect the information, the questionnaires were distributed via the internet among social networks such as Facebook, Twitter, and WhatsApp from the Psychological Research Centre of the Fundación Universitaria Konrad Lorenz. The research team and the communications office of the University collaborated in the dissemination of the survey. Data were collected between June and September 2019. The survey took 15 minutes to respond to, and approximately 70% of those who entered the survey finished it completely. Given that it was disseminated in virtual form, the survey was self-administered. Consistent with Colombian legislation, informed consent forms were requested before the interview. Participants received no compensation for their participation.

Results

KH-Coder software was used to analyse the textual data obtained by the six open questions answered by the study participants. The first four refer to the concept of peace in general, and the last two to the Colombian peace process. The answers to the questions were analysed based on the political orientation with which the participants reported sympathy (right, left, centre, or none). We obtained six co-occurrence networks, corresponding to individual nodes built around semantic affinity with political orientations. Finally, we compared the means of the items evaluating the credibility level of the assertions about the Colombian peace process (disseminated during the 2016 plebiscite campaign) of each cluster of participants by political orientation.

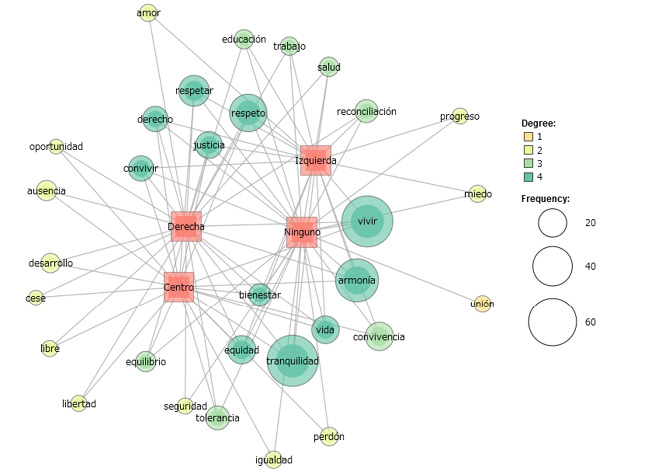

Participants from all political orientation clusters used words such as living, tranquility, and harmony (60 times or more) in their definitions of peace (see Figure 1). Specifically, these words were used in phrases such as: “Peace means living in harmony and tranquility with the people around us.” Less frequently (between 20 and 40 mentions), participants talked about respect, respecting, life, welfare, equity, right, justice, and living together. The word coexistence is the only word used by participants of all political orientations. On the other hand, words such as education, work, health, and reconciliation were used by right-wing, left-wing, and participants who declared having no political orientation. The words tolerance and balance were used by both centre- and right-aligned participants and those having no political affinity. It was striking that other words such as forgiveness, freedom, progress, and love were mentioned in at least two of the political orientation clusters, and the word union was used exclusively by people who said they had no political orientation in sentences such as “union for the same purpose” (with a frequency below 20).

Figure 1. Co-occurrence network for conceptualisations of peace. Squares represent clusters of participants’ political orientation, and circles represent nodes of words most frequently used. The colours of the circles represent the degree of semantic affinity by cluster, from orange (with only one affinity) to dark green (with affinity to four clusters). The network consists of 35 nodes, 90 edges, and a network density = 155. A Jaccard filter (top 90) was used. Analysis units were sentences. Note. Textual data originally analysed in Spanish using KH-Coder software.

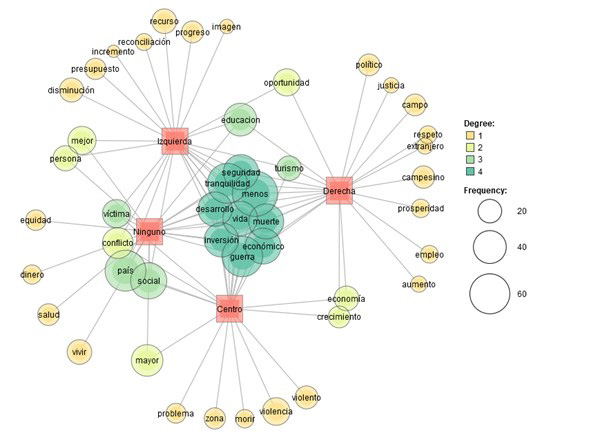

In regard to the benefits of achieving peace (see Figure 2), participants from all political orientations used words such as tranquility, development, life, and especially the word less followed by words like death, war, and other negative aspects related to the conflict. The less frequently used words by three clusters were tourism and education, which are shared by the left, right, and centre clusters; words such as victims, country, and social (which refer to the benefits that the victims and the country would have at the social level) were used by the no orientation, centre, and left clusters. Some words occur in only two clusters; they are oriented toward positive themes; for example, the centre and right clusters use words such as growth and economy, the right and left clusters share the word opportunity, and the left and no orientation clusters share the words conflict, better, and person in reference to the end of the conflict and improvements in people’s conditions, which is evidenced by phrases such as “the end of the conflict and new dreams for Colombia,” or “better quality of life and fewer deaths.” Some words were used in only one cluster, such as problem, zone, and violence, used by the centre cluster in phrases such as “tranquility in the areas affected by the conflict” or “less violence”; words such as justice, countryside, prosperity, and political are used by the right-hand cluster in phrases such as “the countryside becomes a place of development and prosperity” or “real justice and respect for the law.” Words like reconciliation, progress, and resource are used by the left-wing cluster in phrases such as “reconciliation and economic growth” or “availability of resources for investment”; finally, words such as living, health, money, and equity were used by the no orientation cluster in sentences such as “the country would be a better place to live.”

Figure 2. Co-occurrence network for benefits of peace; greater agreement among political orientations is observed in this network. Squares represent clusters of participants’ political stances. Circles indicate nodes for words most frequently used by participants. The colours of the circles represent the degree of semantic affinity by cluster, from orange (with only one affinity) to dark green (with affinity to four clusters). The network consists of 50 nodes, 90 edges, and a network density = 0.073. A Jaccard filter (top 90) was used. Analysis units were sentences. Note. Textual data originally analysed in Spanish using KH-Coder software.

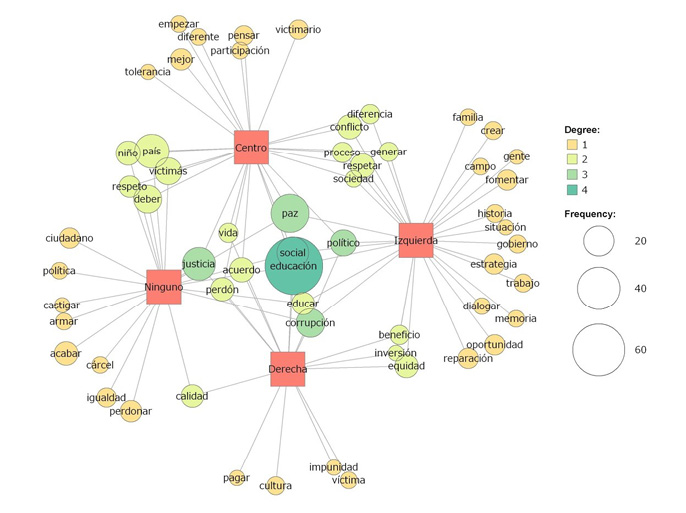

Participants from all political orientations used words related to peacebuilding strategies (frequency = 60 or more, see Figure 3), such as education and social, in phrases such as:

“education as a means of social transformation” or “a social investment based on education.” Words such as justice, peace, politics, and corruption were used less frequently (between 20 and 40 times). The words impunity, paying, and victim were used by participants in the right-wing cluster in phrases such as “I am not one for impunity, the law should be applied, and perpetrators must be punished” or “justice without impunity because the FARC committed terrible crimes, so they must do jail time.” Also, people from the no orientation cluster used words such as jail and punish in phrases such as “former guerrillas must go to jail” and “punish those who have done wrong according to their wrongdoings.” This contrasts with observations from the left-wing and centre clusters, where words such as dialogue, reparation, victimisers, situation, and tolerance were used.

Figure 3. Co-occurrence network for peacebuilding strategies in Colombia. Squares represent clusters of participants’ political stances. The colours of the circles represent the degree of semantic affinity by cluster, from orange (with only one affinity) to dark green (with affinity to four clusters). This network consists of 50 nodes, 90 edges, and a network density = 0.48. A Jaccard filter (top 90) was used. Analysis units were sentences. Note. Textual data originally analysed in Spanish using KH-Coder software.

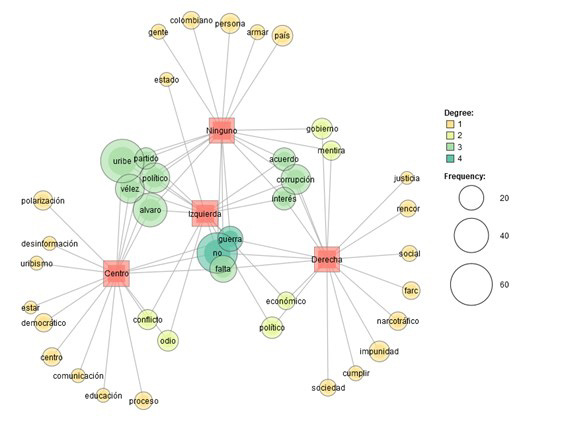

Concerning obstacles to peace (see Figure 4), the words no and agreement were used the most frequently used by participants from all political orientations (60 or more). Specifically, these words were used in phrases such as: “Failure to comply with agreements”, “politicians who do not want peace”, “new armed groups appear every day”, “war continues, and innocent people are sacrificed”. “ Less frequently (between 20 and 40 mentions), the words Álvaro, Uribe, Vélez, politician, and party are used only in the left, centre, and no political orientation clusters. On the other hand, the words interest, agreement, and corruption were mentioned by both right-wing and left-wing participants and by those who declared having no political orientation. The word lack, used in phrases such as “lack of education and sensitivity to the concept of justice,” was used by both centre and right-wing participants and by those who declared having no political affinity. It is striking that other words such as conflict, hate, lie, or government, among others, were mentioned in at least two of the political orientation clusters, and the word State, used in phrases such as “the state is slow to honour the agreement” was used exclusively in the left-wing cluster.

Figure 4. Co-occurrence network for obstacles to achieving peace. Squares represent clusters of participants’ political stances. Circles indicate nodes for words most frequently used by participants. The colours of the circles represent the degree of semantic affinity by cluster, from orange (with only one affinity) to dark green (with affinity to four clusters). The network consists of 44 nodes, 70 edges, and a network density = 0.074. A Jaccard filter (top 70) was used. Analysis units were sentences. Note. Textual data originally analysed in Spanish using KH-Coder software.

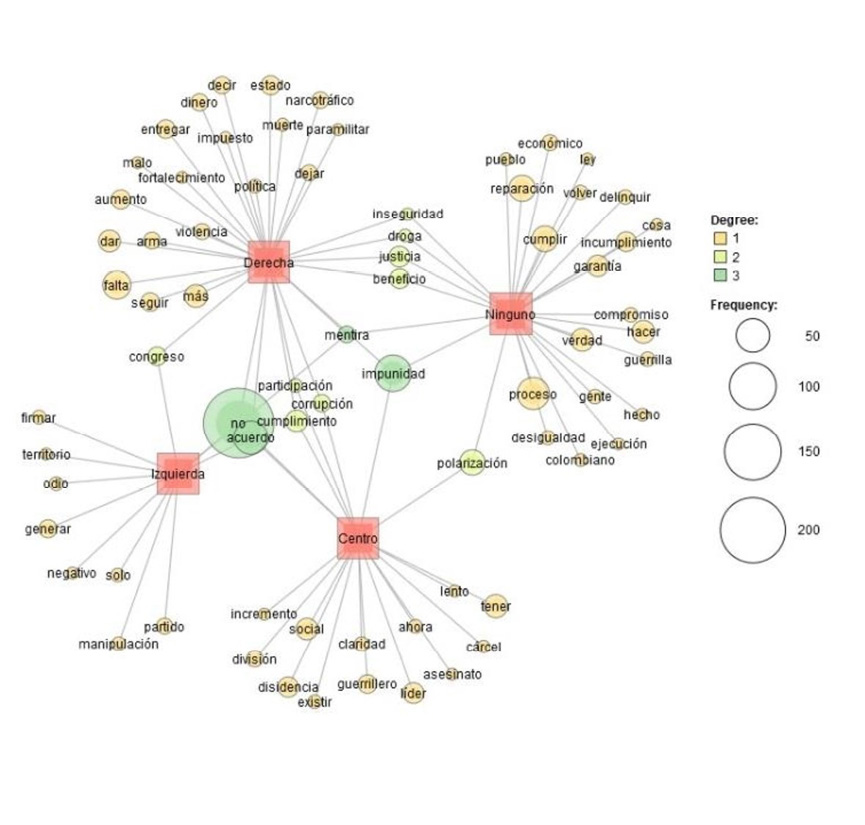

There were no words shared by the four political stances concerning the negative aspects of the Colombian peace process (see Figure 5). The word lie was mentioned by both right-wing, centre-based, and non-political participants. For its part, breach of agreement was mentioned by participants from the right, left, and central political orientations. Other words such as insecurity, polarisation, corruption, and congress were mentioned by at least two of the political orientation clusters; the last word referred to “the involvement of the FARC in the congress without being tried”. Finally, the word manipulation was mentioned exclusively by left-wing participants (frequency under 50) in phrases such as “media manipulation to cater to political positions and the country’s polarisation”.

Figure 5. Negative aspects of the Colombian peace process. Squares represent clusters of participants’ political stances. Circles indicate nodes for words most frequently used by participants. The colours of the circles represent the degree of semantic affinity by cluster, from orange (with only one affinity) to dark green (with affinity to four clusters). The network consists of 77 nodes, 90 edges, and a network density = 0.31. A Jaccard filter (top 90) was used. Analysis units were sentences. Note. Textual data originally analysed in Spanish using KH-Coder software.

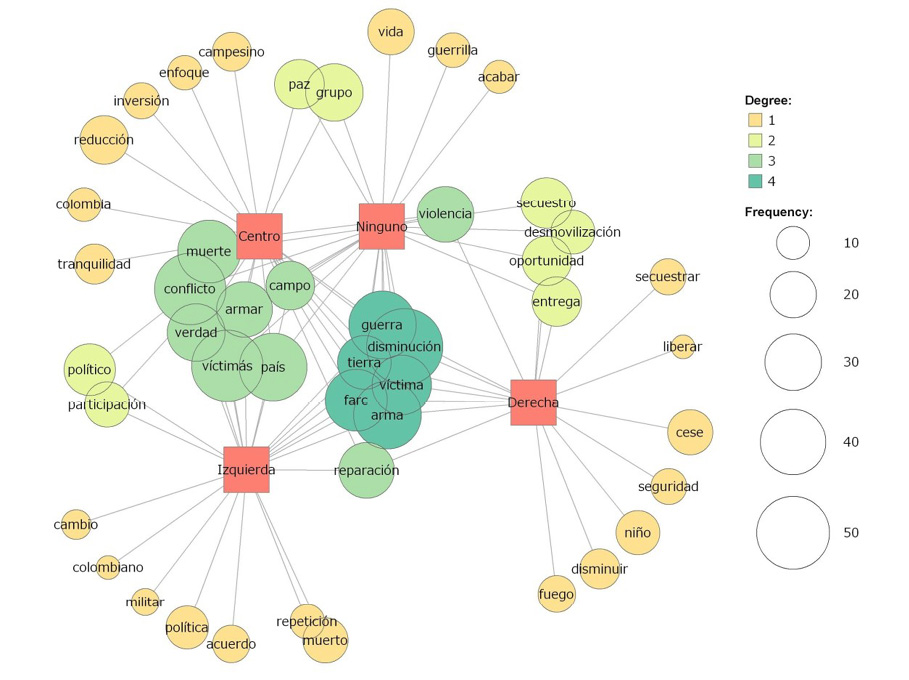

In regard to the positive aspects of the Colombian peace process (see Figure 6), participants from all political orientation clusters used the words decline, war, land, victim, FARC, and weapons with a frequency over 60. These words were used in phrases such as: “Defusing the war against the FARC will make them lay down their arms and allow victims access to land”. The word violence was the only one mentioned by the centre, right, and no political orientation clusters. On the other hand, the words death, conflict, truth, victims, country, arming, and countryside, were mentioned by participants from the left and centre political orientations and by the apolitical participants. Remarkably, the word repair is mentioned by left-, right-, and centre-oriented participants, but not by apolitical ones—the words politics and participation were used in the left and centre political orientation clusters. The words peace and group were used in the centre and apolitical clusters. The right-wing and apolitical clusters include the words kidnapping, demobilisation, opportunity, and surrender in phrases such as “This is an opportunity for the guerrillas to demobilise and surrender their arms so that they can stop the kidnappings”. There were no words shared by the left- and right-wing clusters. These differences are reflected in words mentioned by the left cluster such as military and politics, in phrases such as “political participation of former guerrilla fighters”. Words such as security and defusing were used in phrases such as ”people can walk through their territories more safely”.

Figure 6. Co-occurrence network of positive aspects of the Colombian peace process. Squares represent clusters of participants’ political stances. Circles indicate nodes for words most frequently used by participants. The colours of the circles represent the degree of semantic affinity by cluster, from orange (with only one affinity) to dark green (with affinity to four clusters). The network consists of 50 nodes, 90 edges, and a network density = 0.073. A Jaccard filter (top 90) was used. Analysis units were sentences. Note. Textual data originally analysed in Spanish using KH-Coder software.

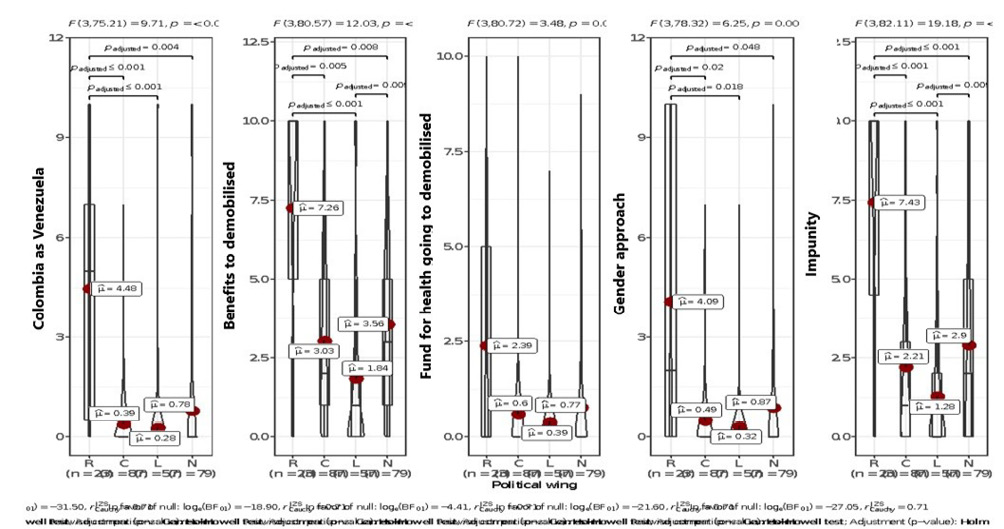

Figure 7 shows the mean differences and distribution of the scores for each of the questions that inquired about the level of veracity given by participants to the following assertions: (a) FARC’s involvement in politics will make

Colombia become like Venezuela; (b) demobilised FARC combatants will receive more benefits than the victims of the conflict; (c) the money used to compensate demobilised combatants is taken from retirement funds for the elderly; (d) the gender-based approach to the peace agreement goes against traditional family values; and (e) the peace agreement signed and endorsed by the FARC favours impunity. In the case of assertion c, the ANOVA variance analysis showed no statistically significant differences among participants from the centre, left, and apolitical orientations. In general, the figure shows that the most marked differences occur between the mean scores of right-wing political participants and the rest of the orientations. Figure 6 shows that both the mean scores and the distributions are higher in all questions in the case of participants whose political orientation is on the right. In other words, for participants who declared having a right-wing political orientation, all statements were considered more truthful than for the rest of the participants.

Figure 7. Mean scores and distribution of scores on the veracity given by participants to some of the statements circulated in Colombian social networks and media regarding the Colombian peace process

Discussion

Peace processes around the world have helped to identify different factors that guarantee the success of peace consolidation processes in territories heavily affected by violence. One of these factors is the support given by civil society to peacebuilding processes. However, in order to guarantee such support, it is necessary to achieve certain levels of cohesion and consensus among citizens regarding peace, its benefits, and the obstacles and strategies for achieving peace, as well as people’s perceptions about the course of the peace process. Additionally, the narratives on social networks and other media have encouraged conflict between people who have different political orientations (including those who claim to have no political orientation or sympathy for any political party).

The first finding of the present study is that, although there is some consensus among citizens concerning the definitions of peace, its benefits, obstacles, and the strategies to achieve it, as well as the positive and negative aspects of the peace process, there are marked differences in their conceptualisations based on their political orientation (Observatorio de la Democracia, 2019).

Concerning the conceptualisations of peace reported by the participants, the words associated with the concept referred to an idea of peace entailing, for example, living in harmony and tranquility. This is consistent with a report by Ramos (2015), who observed that peace has traditionally been defined as a state whose goal is to achieve tranquility and harmony by defeating an adversary in war or improving people’s quality of life. The network of co-occurrences obtained reveals that, as far as the definition of peace is concerned, political orientation is irrelevant. The left and the right, which could be considered the opposite ends of the political spectrum, agree that peace represents education, work, health, and reconciliation, and people from these two political orientations mention love as one of the expressions of peace. The terms in the co-occurrence network show that the definition of peace does not necessarily correspond with the definitions of negative peace but rather with the concepts of imperfect and unfinished peace. Peace operates as a dynamic process requiring the participation of different welfare spheres; López-López (2020) defines it as multidimensional peace (Galaviz, 2013; Menchú, 2016; Ramos, 2015, cited by Gonzales, 2018). Cárdenas (2014) states that equity and access to opportunities, as well as education and optimal health service, are variables associated with the construction of lasting peace and the mitigation of the variables that caused the conflict. The peace conceptualisations network shows the presence of the ideas of coexistence, which refer to the idea that peace is not a series of individual actions but a relationship with the other, undertaking actions such as respecting differences, recognising oneself and others, and following norms (Gonzáles, 2018).

The words tranquility, development, less conflict, less war, security, investment, and life are associated with the benefits of achieving peace, and they were mentioned by participants from all political orientations and by apolitical

participants. These aspects make sense in phrases such as: “as long as there is less conflict, there is more tranquility”. Citizens’ expectations about peace processes are similar to what they consider the benefits of achieving peace. Research has addressed economic conditions after the armed conflict, focusing, for example, on employment and education (Taylor et al., 2016). For instance, a GDP growth of 4% and 6% could be achieved provided there is an increase in foreign investment and production from the rural and touristic sectors (Palacios & Urdaneta, 2017).

Peacebuilding strategies were closely associated with the benefits of achieving peace. In this regard, we observed a frequent and converging reference to education and social investment among the three political orientations and the apolitical cluster. These references emphasise that education is key in peacebuilding contexts, and they highlight the need to strengthen the cultures of peace and social bonds in formal education environments focused on values, attitudes, and behaviours (Villalobos, 2018) and training teachers to lead these processes (Murcia-Murcia, 2018). Different analyses in the present study showed a higher number of convergences between centre, left, and apolitical orientation participants (who refer to

respect for the victims, the need to educate the citizenry, and to the importance of respecting differences and the course of the peacebuilding process), as opposed to those who claimed to have a right-wing political orientation. We also observed that justice plays a fundamental role in peacebuilding processes; other studies have shown that people in violent contexts consider that retributive or procedural justice are the most appropriate methods for reconciliation, as well as sympathisers of political parties that place themselves in the centre or left of the political spectrum and have expressed support for peace agreements (Rodríguez-Pico, 2016), or that restorative justice is better valued than punitive justice when it comes to considering an amnesty (Kpanake & Mullet, 2011; Meto, 2016;Taylor et al., 2016), which entails using peacebuilding strategies based on the search for truth and the recognition of victims and the need for reparations (Taylor, 2015; Torrado, 2017). Interestingly, the gap between political orientations is observed in words exclusively used by certain political opinion groups; for instance, the left refers to the countryside, history, dialogue, memory, and reparation, while the centre talks about participation, tolerance, and taking a different point of view. Apolitical participants referred to forgiveness, equality, punishing, and arming, among others. Finally, the right mentioned impunity and the victims, among other ideas.

Obstacles to peace were also explored in the present study. Predictably, participants mentioned the difficulty for peace to emerge when the war is not over yet. Specifically, participants referred to what Álvarez-Maestre and Pérez-Fuentes (2019) and Rettberg (2003) have pointed out in that persistent violence and war hamper the potential development of peacebuilding efforts. This study shows that, even though sociopolitical violence can become an aspect of everyday life, there are many other forms of violence that are not necessarily addressed in the agreements whose resolution is not the signing of an agreement, no matter how committed the parties are at the time. This study shows that one of the main obstacles to achieving peace—defined as a state of tranquility and harmony—are significant changes needed at all levels of society. Participants indicated that obstacles to peace in Colombia are the lack of compliance with the peace agreement, the interests of political leaders, and corruption. Except for right-wing participants, Álvaro Uribe Vélez and his Centro Democrático party were identified as one of the main obstacles to peace. This political party (to which the ex-president belongs) has advocated for the defense of the status quo, promoting a minimalist version of peace and pressing for important reforms to the peace agreement before congress (Saffon-Sanín & Güiza-Gómez, 2019).

Concerning the positive aspects of the Colombian peace process, we observed that the most frequent ideas shared by all clusters refer to defusing the war and stressing the role of the victims as essential for demanding reparations from their aggressors. This would also have implications for the administration of national resources because approximately 3.4% of the annual Gross Domestic Product would no longer be spent on war. This would result in higher spending on productive and social investments (Fedesarrollo, 2017). Another benefit of the peace agreement mentioned by participants was prompt access to land and the restoration of territories to the victims, which is considered as a positive aspect to support the economic development and self-sustainability of agricultural workers. Another positive aspect mentioned by participants was the decrease in poverty; a return to the territories is expected to help people who were displaced to return to their traditional activities and recover their way of life (CERAC & PNUD, 2014).

Different ideas associated with the negative aspects of the Colombian peace process were also found. The present analysis showed little correspondence between the utterances of participants from different political orientations. None of the mentions found convergence among the four clusters. Right-wing participants considered that the process has strengthened and increased violence and drug trafficking and mentioned the use of tax money to support the peace process and their rejection of FARC political involvement. Left-wing participants referred to new forms of hate and manipulation that have emerged during the process. Centrally-oriented participants mentioned the social division and military action of dissidents, and apolitical participants referred to the failure of the process to honour the agreements and the need to know the truth, assure guarantees, and promote reparations. Participants from the left and centre orientations indicated that both the government and the FARC have failed to honour the agreement; right-wing, centre, and apolitical participants mentioned the impunity of the process; right-wing, left-wing, and apolitical participations mentioned the lies that surround the process.

Finally, we observed a gap between the extent to which the assertions made among media and social networks to discredit the peace process were accepted as true by right-wing participants and the rest of the sample. Right-wing participants were found to be more prone to believe or follow ideas that guarantee the continuation of the status quo (Dávalos et al., 2018)

Limitations

The sample in this study is not representative of the Colombian population as a whole; data were collected online, which excluded many people who do not have easy access to the internet or devices to go online. Additionally, our results depend on the particular conditions of the moment in which the data are collected; therefore, changing political circumstances may change these conceptualisations in the future. Future studies must study the conceptualisations of violence and conflict.

Conclusions

The present study provided evidence of the different conceptualisations of peace based on people’s political orientation. Specifically, differences were found among the participants’ conceptualisations of peacebuilding strategies, obstacles to peace, and the negative aspects of the peace process. Convergences were observed when it comes to conceptualising what peace means, its benefits, and the positive aspects of the Colombian peace process.

Participants who declared themselves as apolitical or having no affinity with any of the existing political parties in Colombia shared their conceptualisations with left-wing, right-wing, and centrally-oriented participants, placing them closer to or farther from these orientations. The fact that most of the people in this study declared themselves to be apolitical is an indicator of their eclecticism or the lack of representation of their interests among current government options.

Political orientation functions as an information filter. It is incorporated into the discourse even when people receive different information that supports or discredits the Colombian peace process. To a certain extent, ideas conveyed by political leaders become elements of identity through which participants support or reject complex processes such as peacebuilding.

Cohesion and consensus problems among civilians can represent a risk to the construction of durable peace and the prevention of a return to conflict (Taylor, 2016b). The findings of the present study highlight the need for cultural practices to bridge the gaps and build bridges between people who have a right-wing political orientation and people with other opinions. Shared perspectives, regardless of political orientation, were also found among the participants; however, these coincidences have been disregarded by political leaders who enjoy credibility among ordinary people, and contrary to expectations, they have used their power to polarise the population.

References

Alcaide, X. M. (2015). Conflicto y paz en Colombia: Significados en organizaciones defensoras de los derechos humanos. Revista de Paz y Conflictos, 8(1), 179-196. https://doi.org/10.30827/revpaz.v8i1.2507

Álvarez-Maestre, A. J., & Pérez-Fuentes, C. A. (2019). Educación para la paz: aproximación teórica desde los imaginarios de paz. Educación y Educadores, 22(2), 277-296. http://dx.doi.org/10.5294/edu.2019.22.2.6

Ávila, A. (2020). Detrás de la Guerra en Colombia. Editorial Planeta.

Azard, E., & Burton, J. (1986). International conflict resolution: Theory and Practice. Lynne Rienner.

Barash, D. (2000). Approaches to peace: A reader in peace studies. Oxford University

Basset, Y. (2018). Claves del rechazo del plebiscito para la paz en Colombia. Estudios Políticos, (52), 241-265. http://doi.org/10.17533/udea.espo.n52a12

Botero, S. (2017). El plebiscito y los desafíos políticos de consolidar la paz negociada en Colombia. Revista de Ciencia Política, 37(2), 369-388. http://dx.doi.org/10.4067/s0718-090x2017000200369

Brett, R. (2017). The role of civil society actors in peacemaking: The case of Guatemala. Journal of Peacebuilding & Development, 12(1), 49-64. https://doi.org/10.1080/15423166.2017.1281756

Caicedo-Atehortúa, J. M. (2016). “Esta es la paz de Santos?”: el partido Centro Democrático y su construcción de significados alrededor de las negociaciones de paz. Revista CS, (19), 15-37. https://doi.org/10.18046/recs.i19.2136

Cárdenas, L. (2014). La construcción de la paz en Colombia: desafíos desde la Escola de Cultura de Pau de Barcelona y la ONU [Ensayo de grado, Universidad Militar Nueva Granada]. Repository Unimilitar. https://repository.unimilitar.edu.co/handle/10654/11524

CERAC & PNUD. (2014). ¿Qué ganará Colombia con la paz?. https://www.co.undp.org/content/colombia/es/home/library/crisis_prevention_and_recovery/-que-ganara-colombia-con-la-paz-/

Cortés, Á., Torres, A., López-López, W., Pérez Claudia, D., & Pineda-Marin, C. (2016). Forgiveness and reconciliation in the context of the Colombian armed conflict. Psychosocial Intervention, 25, 19-25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psi.2015.09.004

Curle, A. (1986). In the middle: Non-official mediation in violent situations. Berg.

Dugand, A., García, C., & Sánchez, M. (2018). Barómetro de las Américas Colombia 2018: paz, posconflicto, reconciliación. Observatorio de la Democracia. https://obsdemocracia.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/MUJERES_USAID_2018.pdf

Dávalos, E., Morales, L., Holmes, J., & Dávalos, L. (2018). Opposition support and the experience of violence explain Colombian peace referendum results. Journal of Politics in Latin America, 16(2), 99-122. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1866802X1801000204

Duncan, G. (2015). Más que plata o plomo. El poder político del narcotráfico en Colombia y México. Debate.

Fedesarrollo. (2017). Informe mensual del mercado laboral: efectos económicos del acuerdo de paz. https://www.repository.fedesarrollo.org.co/handle/11445/3511

Fergusson, L., Hiller, T., Ibáñez, A. M., & Moya, A. (2018). ¿Cómo nos reconciliamos? El papel de la violencia, la participación social y política, y el Estado en las actitudes frente a la reconciliación [Working Paper 239]. Rimisp Centro Latinoamericano para el Desarrollo Rural Colombia, Universidad de los Andes, Centro de Estudios sobre Desarrollo Económico (CEDE). https://ideas.repec.org/p/col/000089/016948.html

Fisas, V. (2010). Introducción a los procesos de paz. Escola de Cultura de Pau, Agència Catalana de Cooperació al Desenvolupament. https://escolapau.uab.cat/img/qcp/introduccion_procesos_paz.pdf

Galtung, J. (1969). Violence, Peace, and Peace Research. Journal of Peace Research, 6(3), 167-191. https://doi.org/10.1177/002234336900600301

García Restrepo, L. (2019). La diplomacia rebelde de las FARC-EP en el proceso de paz de Colombia. Revista CIDOB d’Afers Internacionals, 0(121), 19-43. https://doi.org/10.24241/rcai.2019.121.1.19

García-Vergara, C. A., & Carrillo-Lizarazo, M. A. (2017). Significados, obstáculos y formas de construcción: la paz desde los estudiantes universitarios. Revista Universidad Católica Luis Amigó, 1, 222-241. https://doi.org/10.21501/25907565.2657

Giraldo Pineda, Á., Forero Pulido, C., Córdoba Ibargüen, J. M., López Mejía, A. P., Estrada

Giraldo Ramírez, J. Política y guerra sin compasión. Centro de Memoria Histórico. https://www.centrodememoriahistorica.gov.co/descargas/comisionPaz2015/GiraldoJorge.pdf

Bedoya, G. E., Mutunbajoy Tandioy, T., Sánchez López, A., & Gómez Santacruz, E. G. (2018). Significados de paz para estudiantes de pregrado en Salud Pública y Enfermería. Medellín, Colombia. CIAIQ2018, 3. https://ludomedia.org/publicacoes/livro-de-atas-ciaiq2018-vol-2-saude/

Gonzales, M. (2018). ¿Cómo influye la actitud política del ciudadano en la construcción de la paz en Colombia?. Subjetividad & Sociedad, (3), 1-29. https://portalweb-uniminuto.s3.amazonaws.com/activos_digitales/RAC/Revista+SUBJETIVIDAD+Y+SOCIEDAD/Revista+S%26S+2018-II.pdf

Harty, M., & Modell, J. (1991). The first conflict resolution movement, 1956-1971: An attempt to institutionalize applied interdisciplinary social science. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 35(4), 720-758. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022002791035004008

Hato de Vera, F. (2016). La construcción del concepto de paz: paz negativa, paz positiva y paz imperfecta. Cuadernos de Estrategia, (183), 119-146. https://dialnet.unirioja.es/descarga/articulo/5832796.pdf

Hernández, E. (2009a). Resistencias para la paz en Colombia: significados, expresiones y alcances. Reflexión Política, 11(21),140-151. https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=11011851010

Hernández, E. (2009b). Resistencias para la paz en Colombia. Experiencias indígenas, afrodescendientes y campesinas. Revista de Paz y Conflictos, (2), 117-136. https://doi.org/10.30827/revpaz.v2i0.434

Invamer. Investigación y Asesoría del Mercado S.A.S. (2020). Encuesta Gallup Poll: 25 años del poll (informe n.° 135). https://es.scribd.com/document/481989718/Resultados-de-la-encuesta-Invamer

Kew, D., & John, A. W. S. (2008). Civil society and peace negotiations: Confronting exclusion. International Negotiation, 13(1), 11-36. https://doi.org/10.1163/138234008X297896

Kpanake, L., & Mullet, E. (2011). Judging the acceptability of amnesties: A Togolese perspective. Conflict Resolution Quarterly, 28(3), 291-313. https://doi.org/10.1002/crq.20024

Kriesberg, L. (1997). The development of the conflict resolution field. In W. Zartman, & L. Rasmussen (Eds.), Peacemaking in international conflict: Methods and techniques (pp. 51-77). United States Institute of Peace.

López-López, W. (2020). A multidimensional dynamic perspective of research intervention in peace psychology. Peace Psychol, 29(1), 39-41. https://peacepsychology.org/s/D48_Newsletter_21-July-2020_Compressed_FINAL.pdf

López, W. L., Alvarado, G. S., Rodríguez, S., Ruiz, C., León, J. D., Pineda-Marín, C., & Mullet, E. (2018). Forgiving former perpetrators of violence and reintegrating them into Colombian civil society: Noncombatant citizens’ positions. Peace and Conflict, 24, 201-215. https://doi.org/10.1037/pac0000295

López-López, W., Pineda-Marin, C., Murcia León, M. C., Perilla Garzón, D. C., & Mullet, E. (2013). Forgiving perpetrators of violence: Colombian people’s positions. Social Indicators Research, 114, 287-301. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-012-0146-1

Meléndez, Y., Paternina, J., & Velásquez, D. (2018). Procesos de paz en Colombia: derechos humanos y familias víctimas del conflicto armado. Jurídicas CUC., 14(1). 55-74. https://doi.org/10.17981/juridcuc.14.1.2018.03

Meto, O. (2016). Resumen del acuerdo de paz. Revista de Economía Institucional, 18(35), 319-337. http://dx.doi.org/10.18601/01245996.v18n35.19

Miall, H., Ramsbotham, O., & Woodhouse, T. (2005). Contemporary conflict resolution: The prevention, management and transformations of deadly conflict. Polity.

Moreno, J. D. (2017). Paz, memoria y verdad en El Salvador: experiencias y lecciones para la Colombia del posacuerdo. Análisis Político, 30(90), 175-193. https://doi.org/10.15446/anpol.v30n90.68560

Murcia-Murcia, S. (2018). Análisis de las estrategias del gobierno colombiano sobre la educación rural y los desafíos del pos-conflicto con la firma del proceso de paz en el 2017 [Tesis de grado, Universidad Nacional Abierta y a Distancia – UNAD]. Repository UNAD. https://repository.unad.edu.co/handle/10596/21261

Observatorio de la democracia. (2019) Muestra Especial: Colombia, 2019. https://obsdemocracia.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/ABCol19-v9.2PUB_JR7cJtj.pdf

Palacios, I., & Urdaneta J. (2017). Colombia e Irlanda, predicciones por la paz. Ploutos, 7(1), 14-22. http://dx.doi.org/10.21158/23227230.v7.n1.2017.1756

Palacios, M. (2012) Violencia pública en Colombia, 1958-2010. Fondo de Cultura Económica. https://doi.org/10.4000/nuevomundo.69007

Pérez, M., Vianchá-Pinzón, M., Jerez-Galeano, H., & Martínez-Baquero, L. (2020). Significados de paz en adolescentes y jóvenes víctimas del conflicto armado del centro de Colombia. Tesis Psicológica, 15(1), 1-16. https://doi.org/10.37511/tesis.v15n1a9

Pizarro, E., & Valencia L. (2009). Ley de justicia y paz. Norma.

Pizarro, E. (2018). De la Guerra a la Paz. Editorial Planeta.

Ramos, E. (2015). Paz transformadora y participativa. Teoría y método de la Paz y el Conflicto desde una perspectiva sociopráxtica. Instituto Universitario en Democracia y Paz.

Rettberg, A. (2003). Diseñar el futuro: una revisión de los dilemas de la construcción de paz para el postconflicto. Revista de Estudios Sociales, (15), 15-28. http://journals.openedition.org/revestudsoc/25929

Rettberg, A., & Ugarriza, J. E. (2016). Reconciliation: A comprehensive framework for empirical analysis. Security Dialogue, 47(6), 517-540.

Restrepo, J. A., & Aponte, D. (Eds.) (2009). Guerra y violencias en Colombia: herramientas e interpretaciones. Editorial Pontificia Universidad Javeriana.

Restrepo, E. M., & Bagley, B. M. (2011). La desmovilización de los paramilitares en Colombia: entre el escepticismo y la esperanza. Digitalia Hispánica.

Reyes-Posada, A. (2009). Guerreros y campesinos. El despojo de la tierra en Colombia. Norma

Ricardi, R. (1967). Cómo resolver los conflictos. Interciencia.

Ríos, J. (2017). El Acuerdo de paz entre el Gobierno colombiano y las FARC: o cuando una paz imperfecta es mejor que una guerra perfecta. Araucaria. Revista Iberoamericana de Filosofía, Política y Humanidades, 19(38), 593-618. https://doi.org/10.12795/araucaria.2017.i38.28

Rodríguez-Picó, C. R. (2016). Los partidos políticos colombianos ante los acuerdos de paz de La Habana. Repositorio Universidad Nacional (Ponencia). XII Congreso Chileno de Ciencia Política, 19, 20 y 21 de octubre de 2016, Pucón, Chile. https://repositorio.unal.edu.co/handle/unal/58265

Saffon-Sanín, M. P., & Güiza-Gómez, D. I. (2019). Colombia en 2018: entre el fracaso de la paz y el inicio de la política programática. Revista de Ciencia Política, 39(2), 217-237. http://dx.doi.org/10.4067/S0718-090X2019000200217

Socha, D., Lozano, K., Lozano, M., Guzm.n, K., Torres, B., Daz, D, Duran, Y., Salamanca, P., & Mera, S. (2016). Voces rurales y urbanas del conflicto armado, la violencia y paz en Colombia. Informes Psicológicos, 16(1), 65-84. http://dx.doi.org/10.18566/infpsicv16n1a04

Taylor, L. K. (2015). Transitional justice, demobilization, and peacebuilding amid political violence: Examining individual preferences in the Caribbean coast of Colombia. Peacebuilding, 3(1), 90-108. https://doi.org/10.1080/21647259.2014.928555

Taylor, L. K. (2016a). Impact of political violence, social trust, and depression on civic participation in Colombia. Peace & Conflict: Journal of Peace Psychology, 22(2), 145-152.https://doi.org/10.1037/pac0000139

Taylor, L. K. (2016b). Implications of coping strategies and community cohesion for mental health in Colombia. D. Christie, S. Suffla, & M. Seedat (Eds.), Enlarging the scope of peace psychology - African and world-regional contributions. Springer Peace Psychology Book Series.

Taylor, L. K., Nilsson, M., & Amezquita-Castro, B. (2016). Reconstructing the social fabric amid on-going violence: Attitudes toward reconciliation and structural transformation in Colombia. Peacebuilding, 4(1), 83-98. https://doi.org/10.1080/21647259.2015.109490

Torrado, J. J. V. (2017). Plebiscito por la paz en Colombia, una disputa política más allá del contenido de los acuerdos. MARCO (Márketing y Comunicación Política), 3, 57-76. https://doi.org/10.15304/marco.3.4224

Touzard, H. (1981). La mediación y la solución de los conflictos. Herder.

Tovar, C. C., & Sacipa, S. (2011). Significados e interacciones de paz de jóvenes integrantes del grupo “Juventud Activa” de Soacha, Colombia. Universitas Psychologica, 10(1), 35-46.

Turriago-Rojas, D. (2016). Los procesos de paz en Colombia, camino ¿a la reconciliación? . Actualidades Pedagógicas, (68), 159-178. https://doi.org/10.19052/ap.3827

Ugarriza, J. E., & Pabón A., N. (2017). Militares y Guerrillas: La memoria histórica del conflicto armado en Colombia desde los archivos militares, 1958-2016. Editorial Universidad del Rosario.

Valencia, G. D.,Gutiérrez, A., & Johansson, S. (2012). Negociar la paz: una síntesis de los estudios sobre la resolución negociada de conflictos armados internos. Estudios Políticos, 40, 149-174. https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/164/16429068009.pdf

Vargas-Velásquez, A. (2010). La influencia de los poderes ilegales en la política colombiana. Nueva Sociedad. 225. https://nuso.org/articulo/la-influencia-de-los-poderes-ilegales-en-la-politica-colombiana/

Vargas Velásquez, A. (2009). Conflicto armado, su superación y modernización en la sociedad colombiana. C. Paz y conflicto en Colombia, Universidad Nacional de Colombia. 161-180. https://repositorio.unal.edu.co/handle/unal/71589

Villalobos, Y. S. (2018). Los instrumentos de la cátedra de paz, como estrategia en la reconstrucción social de una nueva Colombia. Revista Experiencia Docente, 5(1), 19-35. http://experienciadocente.ecci.edu.co/index.php/experienciadoc/article/view/74

Zelik, R. (2015). Paramilitarismo violencia y transformación social política y económica en Colombia. Siglo del Hombre Editores.

Appendix A

Considering the implementation of the peace process in Colombia, to what extent do you consider the following statements to be true:

(a) The intervention of the FARC in political matters will make Colombia become like Venezuela,

(b) FARC demobilised combatants receive more benefits than victims of the conflict,

(c) To pay the expenses of demobilised combatants, senior citizens’ pensions are being taken away

(d) The gender-based approach to the peace agreement is against family values

(e) The peace agreement signed and endorsed with the FARC favours impunity.