Effects of COVID-19 on the Honduras National Police and lessons learned regarding police officer well-being and occupational stress

Efectos del COVID-19 en la Policía Nacional de Honduras y lecciones aprendidas sobre el bienestar y el estrés laboral de los policías

Efeitos do COVID-19 na Polícia Nacional de Honduras e lições aprendidas sobre o bem-estar e estresse no trabalho dos policiais

Wayne J. Pittsa* | Christopher S. Inkpenb | Raquel Margarita Ovalle Romeroc | Jesús Guillermo García Irahetad | Omar Alejandro Ventura Rizzoe | Alejandro José Alay Lemusf

a https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4428-2356 RTI International, Research Triangle Park, EE UU

b https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9609-0220 RTI International, Research Triangle Park, EE UU

c https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7130-3901 RTI International, Ciudad Guatemala, Guatemala

d https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4036-539X RTI International, Tegucigalpa, Honduras

e https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2426-7581 RTI International, San Pedro Sula, Honduras

f https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9750-7139 RTI International, Ciudad Guatemala, Guatemala

- Fecha de recepción: 2021-05-13

- Fecha concepto de evaluación: 2021-09-02

- Fecha de aprobación: 2021-09-16

https://doi.org/10.22335/rlct.v13i3.1456

Para citar este artículo / To reference this article / Para citar este artigo: Pitts, W. J., Inkpen, C., Ovalle-Romero, R. M., García-Iraheta, J. G., Ventura-Rizzo, O. A., & Alay-Lemus, A. J. (2021). Effects of COVID-19 on the Honduras National Police and lessons learned regarding police officer well-being and occupational stress. Revista Logos Ciencia & Tecnología, 13(3), 30-45. https://doi.org/10.22335/rlct.v13i3.1456

* Autor de correspondencia. Correo electrónico: wpitts@rti.org

Abstract

Background: In early 2020 a global pandemic linked to a coronavirus, known as COVID-19, quickly spread and Government authorities scrambled to respond implementing travel restrictions, social distancing, testing, and quarantines. By early March, the Republic of Honduras implemented strict protocols, requiring greater attention from the police in enforcing the mobility restrictions and working with Government and public health officials to contain spread of COVID-19. Purpose: The purpose of this formative research is to better understand the impacts of COVID-19 on the Honduras National Police with particular attention to officer well-being and occupational stress. Methods: Using mixed methods, this article reports the descriptive results of 28 semi-structured qualitative interviews with high-level command staff from the Honduran National Police (HNP) and a representative sample of 143 patrol officers drawn from police districts in Tegucigalpa, San Pedro Sula, La Ceiba, and La Lima. Results: Policing activities related to crime prevention, investigations, and human resource assignments have shifted in Honduras due to COVID-19. Few police protocols have been updated to reflect this new work environment and steps to protect the well-being of police officers have been inconsistent, with elevated stress levels among officers. Limitations: This case study of police in Honduras is based on a small but representative sample of line officers. The findings of this study are most useful to neighbouring countries in Central America, though there are findings relevant to all police agencies. Conclusions: Our review and analysis have immediate implications for police agencies working to address planning and training deficiencies during the current COVID-19 outbreak while also underscoring critical considerations to prepare for the next worldwide health crisis.

Keywords: COVID-19, police occupational stress, police wellness

Resumen

Antecedentes: A principios de 2020, una pandemia global vinculada a un coronavirus, conocida como COVID-19, se propagó rápidamente y las autoridades gubernamentales se apresuraron a responder implementando restricciones de viaje, distanciamiento social, pruebas y cuarentenas. A principios de marzo, la República de Honduras implementó protocolos estrictos que requerían una mayor atención por parte de la policía para hacer cumplir las restricciones de movilidad y trabajar con el gobierno y los funcionarios de salud pública para contener la propagación del COVID-19. Propósito: El propósito de esta investigación formativa es comprender mejor los impactos del COVID-19 en la Policía Nacional de Honduras, con especial atención al bienestar de los oficiales y el estrés ocupacional. Métodos: Utilizando métodos mixtos, este artículo reporta los resultados descriptivos de 28 entrevistas cualitativas semiestructuradas con altos mandos de la Policía Nacional de Honduras (PNH) y una muestra representativa de 143 patrulleros provenientes de distritos policiales de Tegucigalpa, San Pedro Sula, La Ceiba y La Lima. Resultados: Las actividades policiales relacionadas con la prevención del delito, las investigaciones y la asignación de recursos humanos han cambiado en Honduras debido al COVID-19. Se han actualizado pocos protocolos policiales para reflejar este nuevo entorno de trabajo y las medidas para proteger el bienestar de los agentes de policía han sido inconsistentes, lo que ha provocado un aumento de los niveles de estrés entre los agentes. Limitaciones: Este estudio de caso de la policía en Honduras se basa en una muestra relativamente pequeña pero representativa. Los hallazgos de este estudio son más útiles para los países vecinos de Centroamérica, aunque hay hallazgos relevantes para todas las agencias policiales. Conclusiones: Nuestra revisión y análisis tienen implicaciones inmediatas para las agencias policiales que trabajan para abordar las deficiencias de planificacLOS ticas para prepararse para la próxima crisis de salud mundial.

Palabras claves: COVID-19, estrés laboral policial, bienestar policial

ResumO

Contexto: No início de 2020, uma pandemia global ligada a um coronavírus, conhecida como COVID-19, se espalhou rapidamente e as autoridades governamentais foram rápidas em responder implementando restrições de viagens, distanciamento social, testes e quarentenas. No começo de março, a República de Honduras implementou protocolos rígidos que exigiam maior atenção da polícia

para fazer cumprir as restrições de mobilidade e trabalhar com o governo e as autoridades de saúde pública para conter a disseminação do COVID-19. Objetivo: O objetivo desta pesquisa formativa é compreender melhor os impactos do COVID-19 na Polícia Nacional de Honduras, com atenção especial ao bem-estar dos policiais e ao estresse ocupacional. Métodos: Usando métodos mistos, este artigo relata os resultados descritivos de 28 entrevistas qualitativas semiestruturadas com altos funcionários da Polícia Nacional de Honduras (PNH) e uma amostra representativa de 143 policiais de patrulhamento dos distritos policiais de Tegucigalpa, San Pedro Sula, La Ceiba e La Lima. Resultados: As atividades policiais relacionadas à prevenção do crime, investigações e alocação de recursos humanos mudaram em Honduras devido ao COVID-19. Poucos protocolos policiais foram atualizados para refletir esse novo ambiente de trabalho, e as medidas para proteger o bem-estar dos policiais têm sido inconsistentes, levando a um aumento dos níveis de estresse entre os policiais. Limitações: Este estudo de caso da polícia em Honduras é baseado em uma amostra relativamente pequena, mas representativa. Os resultados deste estudo são mais úteis para os países vizinhos da América Central, embora haja resultados relevantes para todas as agências policiais. Conclusões: Nossa revisão e análise têm implicações imediatas para as agências policiais que trabalham para lidar com as deficiências de planejamento e treinamento durante o surto atual do COVID-19, ao mesmo tempo em que fazem ênfase nas considerações fundamentais para a preparação para uma futura crise de saúde global.Palabras claves: COVID-19, estrés laboral policial, bienestar policial.

On February 10, 2020, the Honduran Government recognized the potential threat of the coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 (severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2), also known as COVID-19, and declared a nationwide health emergency. By mid-March, a nationwide curfew was established, and the Honduran National Police (HNP) were charged with enforcing restrictions. Now, more than 17 months later, the travel restrictions and curfews remain in place and there have been 321,675 confirmed cases of COVID-19 in Honduras, and 8496 associated fatalities (Worldometer.info, August 18, 2021). This study examines occupational stress and officer well-being for HNP officers in the context of workplace changes resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic.

The police are accountable for preserving public order and protecting citizens, and the policing profession is a stressful occupation even under regular conditions. COVID-related health and emerging occupational stressors have led many Honduran officers to experience much higher levels of on-the-job stress. Because of their inherently close-contact work with the public, including groups most likely to be exposed to infection, police are at greater risk of exposure during a pandemic than

the general population. As a Government agency, the police are unique from other government institutions because of their legal mandate, pervasive community presence, and extensive range of responsibilities. Most importantly, the police are legislatively allowed to implement force to achieve these objectives. In practice, these additional police responsibilities in Honduras

created conditions that significantly impacted occupational stress and workplace conditions for police officers, but also led to inherent shifts in how policing activities are conducted. The purpose of this research is to better understand the impacts of COVID-19 on HNP officer well-being and occupational stress.The COVID-19 pandemic has been preceded by other global health threats including the 1957-58 “Asian flu”, Ebola (first identified in 1976), Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) in 2002-2003, the 2003-2004 “Bird flu” and the 2009 “Swine flu”, but the breadth and length of effects of the 2020 COVID-19 crisis on law enforcement personnel is unmatched. The fact that police officers generally experience especially high levels of occupational stress is well documented (Brown & Campbell, 1990; Liberman et al., 2002). Before COVID-19, law enforcement officers around the world suffered from a greater likelihood of mental health problems due to the overall culture of policing, exposure to traumatic events, threats of violence, long hours and taxing shifts, dissonance with the communities where they work, and low levels of workplace prestige. Elevated stress for police officers is also often linked to poor health outcomes, compared to the general population (Hartley et al., 2011). These stressors also directly contribute to negative coping behaviours including alcohol and drug use, abusive personal and family relationships, depression, and social isolation.

COVID-19 has created widespread uncertainty, fear, and generalized anxiety for much of the world. Certainly, police are not immune to these compounded effects. Their roles as essential workers responsible for enforcing social distancing measures, curfews, and quarantines, exacerbated by their increased exposure to the most vulnerable populations and already stressful workplace conditions, make law enforcement agents especially vulnerable to negative mental health consequences (Stogner et al., 2020; Violanti et al., 2017). As police officers provide a public service to citizens by rendering medical support, providing humanitarian outreach and well-being checks, and fostering police-community relationships, they are often tasked with filling multiple and sometimes conflicting roles in the community in which they work. In Honduras, the normal stressors of policing, compounded by shifting workplace demands and heightened concerns about the physical conditions of the work environment due to COVID-19, have diverted the focus of police from primary prevention and community policing to unique law enforcement patterns. This study seeks to understand the relationship between shifts in police practice and policy due to the COVID-19 pandemic and measures of occupational stress and officer well-being. We explore this question by examining data collected via interviews with HNP police administrators and surveys of police patrol officers. We then turn to considering the implications of COVID-19 for the HNP in four key areas: (1) police-community relations, (2) the mental health and well-being of officers, (3) intra-organizational challenges, and (4) interagency collaboration and cooperation.

This study also contributes to the limited literature on the Honduras National Police. Because of this dearth in

the literature, it is important to understand the context of policing in Honduras. The next sections offer a summary of the organization and distribution of the Honduras Nacional Police. This synopsis includes an introduction to the Modelo Catracho, the philosophy guiding community policing activities. Finally, we present an overview of community trust towards the police and overall police legitimacy as well as some major crime indicators.Study context

The Honduran National Police was founded in 1882, but it was a century later, in 1982, that the organization took its current form, separating from the military to become a national civil force. By September 2020, the HNP had

a total of 18,788 agents deployed in the country, divided into two Metropolitan Prevention Units (Unidad Metropolitana de Prevención – UMEP), which cover Tegucigalpa and San Pedro Sula, and eighteen Departmental Prevention Units (Unidad Departamental de Prevención – UDEP), coinciding with other, more rural, parts of the country. Two-thirds of the police force is divided amongst the three largest divisions: the Division of Prevention and Community Security (45.3 %), the Division for Police Investigations (10.5 %), and the Division for Highways and Transportation (10.5 %). Recent estimates indicate that roughly 80 % of the HNP force is male (HNP, 2020).Each UMEP and UDEP in the country is divided into districts and then subdivided into community-based police substations, known as postas. Though there are some variations, most officers report to their postas for ten days, followed by four days of rest. During their ten days on shift, officers are required to live in on-site barracks at the posta. During each 24-hour period during the ten-day shift, most officers spend 12 hours in uniform on duty followed by 12 hours of on-call status. During the on-call periods, most officers sleep, exercise, run personal errands, and relax, though their movements are loosely monitored by command staff. Officers must be available at a moment’s notice should a need arise while at the posta. While most officers have their own bed, the conditions at many postas require officers from each shift to share common spaces (i.e., bathrooms, showers, dining areas) and crowding is a common concern, even before COVID-19. Du-

ring March and April 2020 vacation time for most officers was revoked, exacerbating space limitations, and sorely impacting the ability to practice social distancing.This article is based on research conducted with officers from the Division of Prevention and Community Security (La Policia Preventiva), the segment of the HNP responsible for responding to direct calls for service and most community policing activities. In Honduras, community policing includes all community-level activities carried out by police designed to prevent, deter, and otherwise address criminal activity to promote citizen security, guarantee the legal rights afforded by the constitution, maintain public order, and promote peaceful coexistence, within a framework intended to respect human rights. The HNP follow the community policing strategy known as ‘Modelo Catracho’, a Honduran adaptation of the community policing model, which prioritizes building relationships between law enforcement officers and the communities they serve. The Modelo Catracho emphasizes neighbourhood-level crime prevention activities, efficient responses to calls for service, building trust and maintaining order through community outreach and public services to assist citizens. Community prevention police officers attempt to prevent and control crime by patrolling neighbourhoods on foot, motorcycle, or patrol vehicle, responding to potentially criminal incidents. These officers seek to promote public order by supervising minor civil disputes, resolving pu-

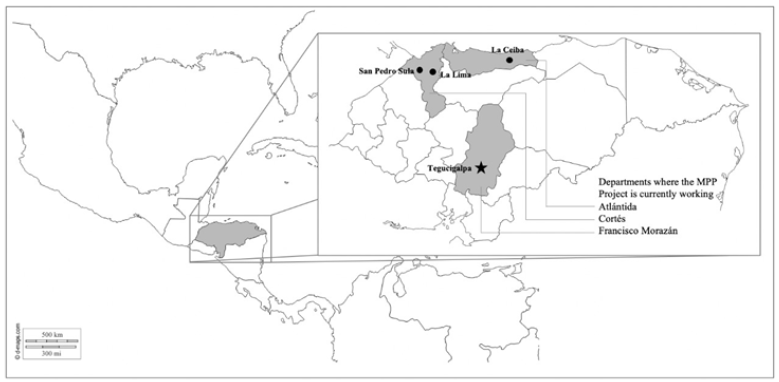

blic nuisances, and assisting and providing security for public gatherings (e.g., parades, sporting events, protest events). Also, each police substation works to establish ties with local community organizations (patronatos) to learn about local priorities and to coordinate responses regarding security concerns. Police accountability to the communities is a critical component of the Modelo Catracho.This article draws upon participant observation from working as a U.S. Government-funded project implementer with the HNP, along with a multi-faceted and mixed methods data collection effort of the HNP carried out by the authors. Aligned with the Modelo Catracho, the Honduras Model Police Precinct (MPP) Project is supported by the United States Department of State, Bureau of International Narcotics and Law Enforcement Affairs (INL) and implemented by RTI International. The MPP project is focused on the departments of Francisco Morazán (UMEP 1 – Tegucigalpa), Cortés (UMEP 2 – San Pedro Sula and UDEP 5 – La Lima), and Atlántida (UDEP 1 – La Ceiba). The Honduras MPP Project is aimed at encouraging a culture of lawfulness to establish the basis for dialogue and respect among the citizens and the HNP. To achieve this, the project provides support to the HNP police through logistical activities, training, and technical assistance. The data for this article are derived from data gathering activities conducted as part of the Honduras MPP project.

Figure 1

Map of Honduras showing MPP focus areas

Note. Author elaboration building on base maps, used with permission. The Central America map is available at: https://d-maps.com/carte.php?num_car=1389 and the Honduras mas map is available at https://d-maps.com/carte.php?num_car=5277

It is also important to consider the overall security conditions and context in Honduras. According to data from the Latin American Public Opinion Project (LAPOP) AmericasBarometer survey, approximately one in five Honduran adults self-reported criminal victimization in 2018, and the percentage has been relatively stable since 2012. Government mistrust is widespread, though improving gradually, according to LAPOP data, and 40 % perceive that government corruption is normal. Satisfaction with public services has been tracking downward since 2012, and half of all respondents in the 2018 LAPOP sample reported that police response times were more than one hour. Satisfaction with public health services has also declined with 62.0 % satisfied in 2012, dropping to 42 % in 2018. Mistrust in the police in 2018 was higher than at any other time

in the nearly twenty-year history of biannual LAPOP surveys, except for 2012. One quarter of all respondents reported that they have absolutely no trust in the police (Montalvo, 2019). Not surprisingly, victims of crime and people who feel more insecure are more likely to mistrust the police. In general, these figures depict a population

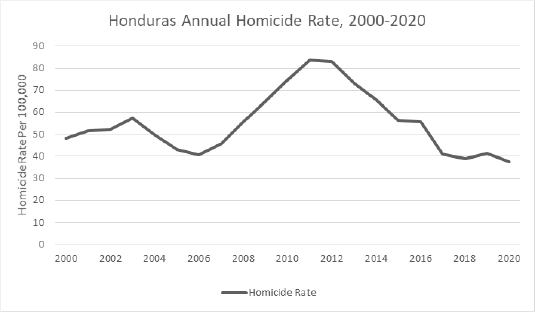

that is dissatisfied with and mistrustful of their police.Figure 2

Annual homicide rate in Honduras, 2000-2020

Note. UNODC (2019); Asmann & Jones (2021).

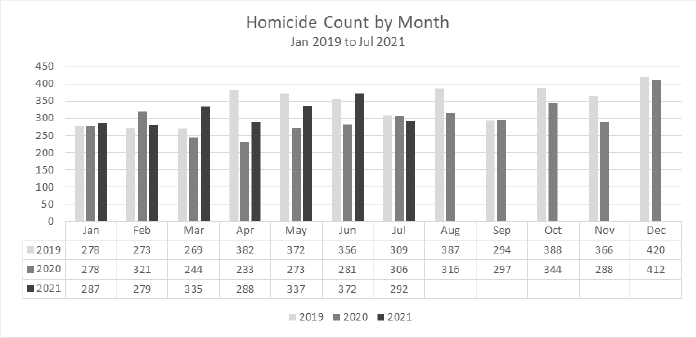

During the last decade, Honduras has frequently appeared among the most violent countries in the world (Asmann & Jones, 2021; UNODC, 2019). Even so, homicide rates have been steadily trending downward, though the rates continue to be very high compared with most of the world (UNODC, 2019). Homicide rates between 2011 and 2018 steadily declined before making a slight upturn in 2019 to 41.2 homicides per 100,000 in the population (see figure 3). During the COVID-19 pandemic, data provided by the HNP show monthly incidents of homicide in 2020 were consistently fewer than 2019 in the first months of the pandemic. In 2019, the daily mean of homicides in Honduras was 11.2, and this dropped to 9.8 in 2020. In 2021, homicides are trending upward, despite the continuation of COVID-19 travel restrictions and curfews. In fact, the number of homicides in March and June 2021 are higher than 2020 and 2019, though the mean for the first seven month of 2021 (10/3/day) is still lower than the 2019 mean (DPPOMC/SEPOL, 2021).

Figure 3

Comparing incidents of homicide during COVID-19

Note. DPPOMC/SEPOL (2021).

Methods

MethodsFormative or learning research is the process by which researchers investigate how to access their target population and describe the attributes of the community that are relevant to a specific public health issue, in this case COVID-19. This formative research is based on two distinct data collection phases and methods. During the first phase, the authors conducted primary interviews with police command staff in May 2020. These semi-structured, qualitative interviews, conducted by telephone, asked administrators to describe their challenges and concerns during the COVID-19 pandemic (i.e., perception of the impact on police activities, shifts in criminal dynamics, physical and emotional health of unit personnel). The objective of this first phase was to conduct a qualitative evaluation of the institutional impact of COVID-19 on the department and to determine what actions were needed to support the department. The results of these interviews in Phase 1 informed the development of a telephone survey instrument (The Honduran National Police COVID-19 Practices Survey) in Phase 2. This survey, administered to lower-level patrol officers, sought to identify changes in police operations, crime trends, and query perceived standards that the officers felt were necessary to do their job activities safely. This phase of data collection was implemented from July 23 to August 28, 2020.

Both waves of collection included data collection activities in UMEP 1 based in Tegucigalpa, UMEP 2 around San Pedro Sula, UDEP 1 in La Ceiba and UDEP 5 in La Lima. These areas account for the most populated areas in Honduras, including the two largest metropolitan areas, and include a representative sample of HNP officers. Interviews were conducted by Honduras MPP project interviewers trained in administering the instruments. Permission to conduct interviews with HNP was first approved by police administrators who then provided a list of staff by district for possible inclusion in the survey sample. While a national sample of all HNP staff or a larger response rate could prove valuable, the agencies who answered the study reflect the range of police stations in terms of number of sworn officers and are representative of crime trends in rural and urban areas of Honduras.

In the first round of data collection with police command staff, we obtained contact details from the Director of the Division of Prevention and Community Security for a purposive sample of 28 police executives with representation from several National Police Units (district headquarters, logistics, operations, and chief of staff). Interviews were prioritized with officers who had knowledge of operational adjustments due to COVID-19 for each unit. Each participant provided voluntary consent to participate in the research. All semi-structured interviews were recorded using the voice recorder application in Windows 10, for subsequent transcription and analysis. Completing the interviews with command staff posed significant challenges because of quarantine restrictions and increased operational activities. A total of fifteen interviews (54 % of the sample) were completed with command staff in the targeted UMEPs and UDEPs. Interviews with the remaining thirteen individuals included in the original sample could not be completed due to internal transfers to other HNP posts, mandatory quarantine restrictions due to exposure, and one senior officer who died due to complications stemming from COVID-19 infection. The information gleaned from these interviews informed the development of the HNP COVID-19 Practices Survey that was used in the second phase of the data collection.

In the second wave of interviews conducted with patrol officers, RTI developed a self-administered survey questionnaire emphasizing the effects of COVID-19, adapting several questions from other international survey instruments related to emergency crisis responses, including pandemics. The multi-topic questionnaire incorporated modules to capture information on the effects of COVID-19 in the operation landscape of policing, impact on police community relations, impact on officer wellbeing, and safety concerns, among other topics.

The sampling frame consisted of a complete list of all HNP personnel with work access to an active phone line. The Director of the Division of Prevention and Community Security provided the contact details for all active patrol officers within the division. According to information provided, which was current through the end of February 2020, the population was 1398, which included 168 women (12.0 %). The researchers drew a sample of 200 police officers, stratified by gender and weighted by population by police stations included in the Honduras MPP project. Patrol officers include police professionals ranked by class, non-commissioned officers, and local/municipal police. All 200 individuals were invited to participate in the study. A total of 143 surveys (71.5 %) were successfully completed. Individuals who were unable to be reached, following at least three attempts, or who refused to participate were replaced in the sample. The final survey response rate was 65.6 %. Importantly, data were collected as part of a project-related surveying effort, and therefore samples were unable to be increased to support finding minimal effect sizes from inferential analyses.

The survey questionnaire was designed to be self-administered for officers with access to the internet through their cell phone data plan, Wi-Fi access, or fixed internet connection. This self-administered survey method was chosen to limit risk of exposure to COVID-19 for both officers and research staff. For officers with limited of no internet access, a trained staff member from the MPP Project team conducted the survey by telephone. The data were captured using Google Forms, an application authorized by RTI International for registering responses online. The data were then exported into statistical software for analysis.

For the qualitative phase of data collection, a report of each completed interview was made with notes and perceptions of the interviewers during the application. Qualitative coding was carried out based on the interview notes and transcripts. To synthesize the findings, a descriptive analysis was written using the coded data and topic categories for the interview script.

Results

ResultsThe results of the structured interviews reveal five key findings for consideration. First, and not surprisingly, the Honduran National Police were unprepared for their central role for responding to the pandemic. “We are prepared to fight crime, but not for a crisis like this one”, said one Inspector, pointing out the need to address training and specific functions of police to support social problems

and state emergencies. This health crisis has underscored the importance of the police institution and its more comprehensive participation in social issues. Second, already limited funding was stretched even further during the crisis, which affected the ability to purchase high quality protective equipment for officers. A top administrator lamented: “There have always been needs…when the virus began, we had to rethink our operational strategy on how to protect officers. We just don’t have the resources we need to meet the WHO [sic] recommendations”. Third, the police agency had no contingency plans in place to support police personnel who suspected viral exposure or who became ill.Yes, when a police officer gets sick, I have to beg for medical support at the public clinics and hospitals to get services for my team. We had one sick officer that we couldn’t find help for. What did we do? We had to pool our resources and take him to a private facility just to keep him from dying.

Based on their experiences and observations during the first months of the pandemic, the police supervisors consistently reported perceived shifts in criminal activity with decreases in extortion, robberies, and homicides, and increases in domestic and intrafamilial violence, though drug trafficking networks continued to operate regularly. Data from the National Emergency System indicated that during March-April 2020 there were 20.0 % fewer reports of crimes against property and 27.0 % fewer reports of crimes against life, compared to March-April 2019. Lastly, the results of the semi-structured interviews showed that police workloads dramatically increased following the lockdown requirements announced by the Government. Subjects attributed this increase at least in part to requirements for expanded police checkpoints at the municipal entry and exit points to monitor travel restriction compliance. Besides investing significant resources into community public health campaigns by distributing informational flyers in communities, police also worked to establish sanitary perimeters around medical facilities and supported the national forensic and public health agencies in the disposal of victims’ bodies. All the supervisors surveyed expressed their concerns about the cumulative toll on the physical and emotional health of the police force because of these activities. Informed by the responses of these command staff, the second phase of this study examines the impact of COVID-19 on the individual experiences of patrol officers.

Table 1

Distribution of the universe and sample by sex

Police Unit

Universe

Sample

Total

Male

Female

% of total

populationTotal

Male

Female

UMEP-1

583

503

80

41.7%

83

73

10

UMEP-2

643

594

49

46.0%

92

81

11

UDEP-1

52

45

7

3.7%

7

7

1

UDEP-5

120

103

17

8.6%

17

15

2

Total

1398

1245

153

100%

200

176

24

This section presents the results of the Honduran National Police COVID-19 Practices Survey, the second phase of police data collection, which features responses from 143 police personnel. As seen in table 2, most of the sample are male patrol officers, although the sample does include police leadership at varying ranks. As described above, this sample was collected purposively from urban areas with high crime and greater than average police presence. A plurality of respondents is from districts in the Honduran capital of Tegucigalpa (47 %), followed by districts from San Pedro Sula (44 %), La Ceiba (3 %), and La Lima (6 %).

Table 2

Selected sample statistics (shown in percentages)

Sex

Female

16

Male

84

Mean age

30

Educational attainment

Primary education

3

Secondary education

92

Post-secondary education

4

Rank

Patrol officer

79

Police - Class I

15

Police - Class II

1.4

Police - Class III

1.4

Subaltern Class

0.7

Police Leadership

0.7

Sub-inspector

1.4

Inspector

0.7

District

Tegucigalpa:

Los Dolores

14

Colonia San Miguel

8

Suyapa

14

Kennedy

10

San Pedro Sula

Lempira

6

Guamilito

8

Chamelecón

6

Cofradía

7

Satélite

10

Soncery

7

La Ceiba

La Ceiba District

3

La Lima

La Lima District

6

Note. HNP COVID-19 Practices Survey, N=143.

The survey turns to questions regarding the practical changes to police practices because of the COVID-19 pandemic. As seen in table 3, on average police are reporting receiving nearly two full days less rest per month. Moreover, the great majority of police surveyed indicate that at least one major change has occurred to their daily work activities, with only 14 % of those interviewed indicating that they have experienced no change. Indeed, more than half of police surveyed suggest that they are experiencing increases in required patrols, and nearly a third of respondents indicate they are spending more time dealing with COVID-specific complaints (e.g., transporting people to hospitals, enforcing mask regulations, or maintaining social distancing at stores). In concert with this increase in patrols, 1 in 4 officers also indicate that they have fewer community-related activity and are in less direct contact with citizens, which reflects less opportunity to build community relations, which is important in a sample of “prevention police” that are community-facing. Moreover, about 13 % report having less direct contact with community members and less time for citizen concerns. When asked how respondents’ jurisdictions have changed, 85 % noted that there are simply fewer people in public places due to fear of COVID-19. Although a minority of police report an uptick in signs of social disorder (e.g., vandalism, homelessness, and public consumption of alcohol), a majority indicate that they are dealing with fewer traffic accidents compared to pre-pandemic policing. These findings suggest shifting workplace demands in response to COVID-19.

While most officers (87 %) report that the command staff has taken specific steps to avoid workplace spread of the disease, more than half report (53 %) these steps are insufficient. This dissonance is an important factor impacting overall job satisfaction, and contributes to officer stress. Perhaps most importantly, 58 % of officers surveyed reported they had not received any special training or specific information on how to prevent the spread of COVID-19.

Table 3

Questions related to changes in police practice due to COVID-19 (answers in percentages)

Average reduction in rest days (days)

1.8

Changes noted in regular work duties due to COVID

No change

14

Less community activity, less direct contact with citizens

25

Less citizen attention

13

Covering shifts for police who are reporting as sick more regularly

13

More time patrolling

52

More time dedicated to helping citizens affected by COVID

31

More responsibilities related to cleaning

12

Changes observed in respondents’ beats

No change

3

Greater gang activity

13

Fewer people in public spaces due to fear of crime

35

Fewer people in public spaces due to fear of COVID

85

More vandalism

12

More homelessness

19

More people buying and consuming alcohol

17

More illegally parked cars

18

Fewer traffic accidents

56

Have police leadership taken measures to avoid

workplace spread of COVID?No

13

Yes

87

Were the measures taken sufficient?

No

53

Yes

23

Maybe

24

What measures were taken to control the spread

of COVID-19 in the workplace?

No changes

0

Using masks

99

Physical distancing

48

Hand washing

80

Deep cleaning of facilities

70

Use of antibacterial gel

93

Cleaning and disinfection of patrol cars

65

Isolating high-risk personnel or those with symptoms

41

Restriction or changes of police activities

13

Have you received special training or information on how to prevent the spread of COVID-19?

No

58

Yes

42

Note. HNP COVID-19 Practices Survey, N=143.

As shown in table 3, nearly 87 % of those surveyed reported that police leadership have instated some type of change to stem the spread of COVID-19 in the workplace, although more than half suggest these measures have been insufficient. When detailing the specific practices, nearly all respondents report wearing masks (99 %) or using antibacterial gel (93 %), followed by increased hand washing (80 %) and more emphasis on deep cleaning of police facilities (70 %) and patrol cars (65 %). Importantly, only 13 % noted that actual police protocols have changed, with less than half reporting the implementation of social distancing within offices. Moreover, only 42 % reported having received special training on implementing police operations in response to COVID-19.

Table 4

Questions related to personal changes due to COVID-19(answers in percentages)

What personal difficulties have you faced as a result of COVID-19?

using public transport on rest days

52

paying for public transport

13

access to food

31

access to store and services

48

lowered quality of available food

4

seeing and contacting family

45

stress about exposing oneself to COVID-19

26

stress about exposing family members to COVID-19

43

worry about job stability and possible firings

2

How has your stress level changed during COVID-19?

Increased

69

Decreased

4

Stayed the same

27

What measures have you taken to cope with

stress related to COVID-19?Avoiding reading or watching the news

41

Exercising more than normal

51

Maintaining communication with friends and family

59

Sharing time with pets

1

Practicing religion

34

Meditation or yoga

5

Consuming more alcohol

2

Following police guidelines

37

Support from colleagues

59

Note. HNP COVID-19 Practices Survey, Total N= 143.

Table 4 provides a clearer explanation of how COVID-19 has touched the personal and work lives of officers and increased occupational stress. The effects of COVID-19 for police extend well beyond shifts in policies and practices and the additional strain caused by mandatory shifts and the cancelling of all leave. The personal toll the pandemic has on officers includes many additional factors. For example, most officers travel long distances between their homes and where they posted for work. With public transportation largely unavailable, more than half of officers (52 %) had difficulty returning home during their limited time off. Basic needs were also affected. Even though the HNP provides meals for on duty officers, nearly a third (31 %) expressed difficulty in accessing food for themselves and nearly half (48 %) reported increased strain due to limited access to goods available for sale in stores because of closures and reduced stock levels. While only a quarter of police report fear

of exposing themselves to the virus, 43 % indicate fear of spreading the disease to family members. Seven out

of ten police officers (69 %) surveyed said their stress level have increased in response to COVID-19. In response, a majority cite that they cope with this stress by drawing on support from colleagues (59 %), maintaining communication with friends and family (59 %), or exercising more than normal (51 %). These results suggest a police force that is experiencing substantial shifts in practices, if not policy, and a concurrent increase in an already elevated level of occupational stress. The next section considers the implications of these findings in numerous settings. Discussion

DiscussionUnderstanding the complex effects of the current pandemic on law enforcement agencies in general and police officers specifically requires a formative research strategy, one that considers both personal stressors and on-the-job factors. The COVID-19 crisis continues to unfold and present evolving challenges to the HNP, but there are some lessons-learned from previous events that are useful in regard of anticipating challenges and establishing best practices for responding. A systematic review of 72 studies looking at the short- and long-term effects of disasters and public health emergencies on police agencies conducted by Laufs & Waseem (2020) found that the predominant issues could be categorized into four areas: police-community relations, the men-

tal health and well-being of officers, intra-organizational challenges, and interagency collaboration and cooperation. In the following sections, these are considered in the context of COVID-19 with a focus on Honduras.Police-community relations

The HNP have made a concerted effort to improve community relations, specifically through the adoption and implementation of their community policing strategy, the Modelo Catracho. Prior to COVID-19, the HNP was actively participating in a variety of community outreach activities, designed to increase trust in the police and promote a greater willingness to report crimes to the police. With restricted movements, limited access to personal protective equipment, restrictions on group gatherings, these activities have mostly been suspended due to COVID-19. However, with support from international funding sources, the HNP have continued to do limited door-to-door canvassing of neighbourhoods to meet neighbours and promote crime prevention strategies. One example of this is the Bolsas Comunitarias Program, funded by the U.S. Department of State, where HNP officers purchase and distribute much needed groceries and supplies to poor and underserved communities while focusing on increased police visibility, promoting trust in the police, and increasing opportunities for citizens to report crimes.

Research has shown that constant media coverage during the pandemic has tended to focus on exposure to extreme adversity, leading to exaggerated feelings of risk (Ungureanu & Bertolotti, 2020). This is certainly the case in Honduras and police, as front-line workers, are often forced to sort through Government mandates and persistent media reports. Community rumours and gossip, fuelled by often inconsistent media reports and biased messages from political leaders, have created significant uncertainty and placed police in an uncomfortable position of attempting to explain often-confusing Government messaging. Krause et al. (2020) call out the critical importance of misinformation during COVID, referring to this phenomenon as a misinfodemic, arguing that different actors experience varying risk perceptions, with the police being no exception. Importantly, misinformation is multi-layered and may affect officers in different ways depending on which role they are performing (i.e., first responder, co-worker, family member).

Shifting crime and service patterns also affect police activities and community relations. The travel restrictions and other measures imposed due to COVID-19 have had immediate impacts on illicit organized crime activities in Mexico and Central America including money laundering, extorsion, drug trafficking, and smuggling activities. Because of the shifting trafficking routes and product demands, drug cartels and other criminal networks are developing new strategies. In Honduras, during the early weeks of the pandemic, gangs seemingly relaxed many of their activities and encouraged members to avoid exposure to the virus (ACLED, 2020). The heavy police presence during the enforcement of travel restrictions likely had an immediate impact on street-level gang activity. However, according to the Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime, gangs have made it known that extortion payments suspended during the quarantine would be assessed retroactively once the virus spread is under control (GI-TOC, 2020).

Gender-based and intrafamilial violence has increased during the COVID-19 pandemic in Central America (Ovalle, 2020). Data from the HNP show that assaults resulting in injuries of women increased 22 %, while similar assaults with injuries of men decreased (-16.7 %) during the first three months of 2020 (UNDP/USAID, 2020). Public health crises often amplify gender inequalities and exacerbate violence against women and girls, especially in developing countries, where food insecurity and inadequate and overwhelmed public health agencies coincide to exacerbate safety concerns (UNICEF Help Desk, 2018). This emerging pattern of victimization merits further study as the HNP works to adapt to fluid criminal adaptations and police responses.

Some researchers suggest that smaller criminal enterprises with fewer resources for withstanding the short-term economic pressures of the COVID-19 crisis will likely adapt their focus to generate immediate income streams through looting and direct attacks on business or through adapting to emerging medical markets, providing black market personal protective equipment (PPE), medicines, and/or vaccines to respond to the crisis (Morfini, 2020). While the crisis continues to unfold, police throughout the region will be forced to adapt to the changing balance between organized crime competitive interests, shifting geographies, and black-market adaptations.

The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) estimate nearly a quarter of a million people in Honduras are considered internally displaced, forced out of their homes due to violence. As the current crisis unfolds, the Commissioner warns that criminal groups are taking advantage of COVID lockdowns to strengthen their control over communities, including through extortion, drug trafficking and sexual and gender-based violence, and using forced disappearances, murders, and death threats (UNHCR, 2020).

It is clear police-community relations in Honduras are strained because of the effects of the COVID-19 crisis. However, the pandemic offers the prospect for police to strengthen and, in some cases, rebuild lost legitimacy in the communities where they work. Policing research shows that trust in the police and attitudes regarding police legitimacy has serious implications for citizen satisfaction, law abiding behaviour, and for improving overall perceptions of the rule of law (Bottoms & Tankebe, 2012; Jones, 2020; Mazerolle et al., 2013; Terrill et al., 2016). How the police respond to the COVID-19 pandemic, as Jones (2020) asserts, will likely take either one of two directions: heavy-handed enforcement strategies, that deepens rifts between law enforcement and communities, or police will embrace empathetic, procedurally just approaches that promote police legitimacy and strengthen community trust. For instance, Amadsun (2020) has documented the increase in human rights abuses by police across several African countries stemming from political indifference and grossly inadequate public health infrastructure to respond to the COVID-19 crisis. Plagued by a history of human rights abuses and misuse of police authority, the HNP are working to address community trust concerns and improve police legitimacy.

The mental health and well-being of officers

One of the key challenges for the HNP and other police organizations worldwide is how to ensure that the officers themselves are protected from infection and afforded the necessary administrative support to continue to do their jobs. Police stress, office mental health, and strengthening resiliency are of paramount importance. In 2017, Violanti and colleagues published a wide-reaching summary of police officer occupational stress and associated psychological and physiological health outcomes (Violanti et al., 2017). In addition to the “normal” stresses associated with being a police officer in Honduras, during the COVID-19 crisis, HNP officers have been subjected to huge and constantly shifting workloads, long shifts, worsening work conditions, concerning media reports (exacerbated by sorting out hyperbole and misinformation), erratic organizational policy shifts and Government mandates, and the persistent reminder of new cases of infections and patient deaths. Additionally, officers are aware of their heightened risk of exposure, including the potential for intentional contamination of officers, and this substantially impacts their anxiety (Jennings & Perez, 2020). Finally, as the “face of the Government” in the community, police officers are sometimes subject to public ridicule and tense public confrontations. Any of these experiences can trigger negative feelings such as anger, annoyance, tension, and frustration, and they can intensify police officer stress, concerns about risk, and lead to burnout. (Ungureanu & Bertolotti, 2020).

Untrained to deal with this exact confluence of factors, and with no prior norms or practice to inform their responses, officers are at risk of responding with negative coping behaviours that threaten to erode public trust or result in officer misconduct (Stogner et al., 2020). In early August, as part of the MPP Project, the HNP implemented a special program for officers designed to promote emotional selfcare and stress management strategies to relieve workplace stress and anxiety and offer officers an opportunity to decompress by sharing feelings and discussing concerns.

Intra-organizational challenges

COVID-19 has underscored the organizational frailty of many agencies struggling to respond to the pandemic, not only in public health and other medical institutions, but also emergency response agencies, including law enforcement (Ungureanu & Bertolotti, 2020). From the outset of the crisis, the HNP has sought to balance

the competing demands of the organizational duties and human resource limitations. Consider, for example, the number of 911 calls-for-service in 2019 compared to 2020: in March, 2020, 911 calls increased more than three-fold, from 15,532 calls to 50,668 calls (+327 %), and April had a 386 % surge (62,561 calls), compared to the same months in 2019. Stogner et al. (2020) suggest that stressors stemming from COVID-19 may impact on officer productivity and affect overall job commitment, what could result in officer turnover. As a result of added workloads related to COVID-19 responses law enforcement may be distracted from normal duties and be unable to achieve the same levels of productivity in the field. Also, the personal protective equipment in use to reduce exposure may also distract officers and make them less efficient in carrying out the responsibilities (Stogner et al., 2020). Cancelling leave and extending shifts early in this predicament, the HNP administrators recognized the toll of these actions as absenteeism and complaints from officers increased and soon, officers returned to mostly normal visits with family.COVID-19 has impacted the HNP’s normal rhythms of work. Training programs, roll call activities, and other meetings and gatherings of officers have been significantly curtailed or suspended. Policing agencies are challenged to keep existing duties related to maintaining order and to continue policing operations while facing increased human resource and supply strain (Laufs & Waseem, 2020). The HNP response to COVID-19 has also affected how calls for service are dispatched, how investigations are conducted, which types of enforcement activities are prioritized, and how public access to police facilities has been restricted. All of these activities, impacted in a very short amount of time, have sent shock waves through the entire organization.

The HNP have reassigned personnel, including officers normally assigned to administrative roles, investigations, etc., to help manage new tasks required by the pandemic, including expanded patrols, strategic vigilance of high-risk targets, and increased visibility in high traffic areas to help maintain public order. Other research suggests that some police agencies have experienced opportunistic differences with some lower rank officers being assigned to higher risk jobs with increased potential COVID-19 exposure. On the other hand, overly enthusiastic and less experienced officers may underestimate safety risks and expose the entire team to threats (Ungureanu & Bertolotti, 2020). Reallocating police human resources and other types of adjustments are currently being tracked and documented and will undoubtedly be subject of additional research (PERF, 2020).

Interagency collaboration and cooperation

The HNP has been working in concert with public health officials to protect the public. Perhaps one of the most challenging aspects of the COVID-19 crisis for the HNP has been the enforcement of the Government mandates and public health restrictions. Policing responses can lead to the criminalisation of the most affected communities and significantly impede containment and compliance efforts. This has been even more challenging in rural areas, where public information and clear communication has been more limited (personal correspondence with a high-ranking official within the HNP, May 2020). Ensuring compliance with new regulations and restrictions can be especially challenging and it is important for police to understand citizens’ behaviours and to recognize that certain communities will experience the effects of these policies disproportionately (Laufs & Waseem, 2020; Shirzad et al., 2020).

Study limitations

Study limitationsThe findings of this study should be considered in light of some limitations. This study was implemented during an extraordinarily challenging time for the Honduras National Police, with limited space, shifting work assignments, anxiety regarding exposure, and deep concerns about the economic impacts of the COVID-19 crisis. Participating in this formative research study was, for some, just another example of how the pandemic has impacted their lives. The analysis presented here is largely descriptive, as more complex multivariate analyses were not warranted based on the sample sizes required to detect effects. As a robustness test, the authors conducted a serious of inferential analyses to query the relationship between officer wellbeing, personal stressors, and shifts in practice due to the COVID-19 pandemic. These analyses are omitted, given that the sample sizes required to detect medium or large effect sizes in the sample is unavailable. Exploratory factor analysis and other inferential models did not explain significant variance in the potential dependent variables, (i.e., stress, job satisfaction). Given that the original purpose of this data collection effort was a formative research, designed to gather baseline data to support the design and implementation of an intervention aimed at addressing increased police officer stress resulting from the pandemic, this study provides important context for further analytical research examining the impact of COVID-19 on officer-wellbeing.

Conclusions

ConclusionsFrom the beginning of the COVID-19 outbreak, it was clear that police agencies around the world were ill-prepared to respond to public health recommendations. Basic training on health and safety precautions relating to viral transmission and communicable diseases, and instructions on the proper use of protective equipment are critically needed. The Honduras National Police have an opportunity to implement infrastructure to significantly improve alternative virtual formats for common, traditionally in-person, police activities, including in-service training, community crime prevention events, certain report-taking activities, virtual forums, conference calls, and community surveillance through camera monitoring centres.

The unprecedented COVID-19 pandemic has exposed the police’s dependence on community partners and organizations to promote crime prevention, especially in Honduras (Campbell, 2020). Neighbours, friends, and family were always likely “the first to know” about intrafamilial violence victimization, but now, the hope that someone else will do something, is less likely than ever. Intrafamilial violence was a grave concern before COVID-19 and the HNP now, perhaps more than ever before, need the involvement of communities and key stakeholders to help protect victims. Also, additional training for law enforcement, first responders, physicians and other healthcare personnel need to be made aware of the potential for increased victimization and how to recognize the signs of intrafamilial violence during the COVID-19 pandemic, so they can respond appropriately (Boserup et al. 2020; Bullinger et al. 2020). Meaningful and sustained partnerships with community stakeholders will allow these groups to consolidate their knowledge and resources for a more effective response to future crises.

There is also a need to recognize the unique requirements of rural policing activities and a possible bias in public health responses during a pandemic. Many of the recommendations that have been suggested for police departments are for urban setting, locations where there are more personnel and greater resources for protective measures (Hansen & Lory, 2020). Nearly three-fifths (58.4 %), of the total population of 9.2 million people, reside in urban areas, especially Tegucigalpa (estimated 2020 population of 1.4 million) and San Pedro Sula (~903 K). Based on these figures, nearly four million persons live in rural areas distributed across 100,000 square kilometres. These areas are characterized by higher poverty rates, limited potable water resources, less sanitary conditions, scarce hospital beds, a lack of electricity, deep mistrust in Government agencies, fewer roads, underdeveloped tele-communication networks, inadequate community service providers, and a higher proportion of marginalized, indigenous residents (CIA, 2020). The reach of Government to provide public services, including police support and services for victims, is notably limited. On the other hand, police outposts in these areas may have been impacted less by the COVID-19 pandemic due to greater community resilience and more reliance on service- and prevention-oriented policing. Special consideration of community policing and the effects on COVID-19 on rural, underdeveloped communities is warranted.

There is a need for training and capacity building for police in gender-based and intrafamilial violence, considering emerging trends related to COVID-19. This should also include specialized formation to address the vulnerabilities of the lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) communities in Honduras. As the public health front line response to COVID in many areas, police should be prepared to understand and identify special public safety and security issues affecting both women and children. The HNP and their public health counterparts need to be trained to understand the importance of women as conduits of information across communities and therefore, special messaging targeted towards women regarding public health matters related to COVID and crime prevention strategies should be developed. As the role of primary caretakers often falls to women, public health messaging through police outreach should address these concerns with an explicit lens of gender to promote healthy responses, while being careful not to reinforce gender stereotypes.

Key aspects of community policing strategies in Honduras shifted during the first few months of the COVID-19 crisis. Preventative police officers were reassigned to address travel restrictions, reducing their focus and attention on certain lower-level crimes, and restricting public access to police substations. Community outreach and crime prevention activities were suspended, and police calls-for-service were prioritized. Warranted concerns about contagion due to police substation crowding and the inability to practice social distancing, but also exposure to infected community residents and lowered job satisfaction made anxious officers reluctant to approach community policing activities in the same manner as before. A new normal is evolving within the Honduras police force and key aspects of the Modelo Catracho will change and some programs previously embraced will likely be permanently cancelled. Dismantling these bridges of support and reducing police presence will weaken ties with communities and erode the confidence in the police that has been arduously constructed in recent years. Also, less community policing will reduce contextual knowledge of the communities the police serve, impacting their ability to be proactive in addressing emerging criminal activities and to identify new actors.

In 2006, the Police Executive Research Forum (PERF) hosted a “Pandemic Influenza Symposium” to underscore the importance of planning for an inevitable influenza pandemic. As a follow-up, PERF conducted in-depth case studies of four police departments underscoring the critical importance for police agencies to plan for pandemics and prepare their department to continue operations, protecting their officers as well as the community (Luna et al., 2007). COVID-19 will have residual, persistent impacts on Honduran society and the HNP. Undoubtedly, new policies and procedures will be permanently implemented that will forever alter how the police conduct their field duties. Public relationships will need to be re-established and maintained through adapted community policing techniques. Additionally, COVID-19 stressors have underscored the already hectic conditions of the job and the need to implement specific programming to mitigate the detrimental effects of workplace stress and anxiety experienced by officers.

Two key points are clear going forward in Honduras as the new COVID-19 impacted world evolves: (1) despite resource constraints and competing priorities, the HNP must address officer safety and prepare for the next crisis. Stockpiling protective equipment for a variety of emergency scenarios is logistically complicated and expensive, but nonetheless, essential; (2) officer wellbeing, including both physical and mental health wellbeing, must be prioritized. Current levels of stress and anxiety, which are especially high, must not become the norm and the HNP should make plans to continue efforts already initiated to address police workplace stressors and implement positive coping strategies. In-service trainings and academy activities have been affected by the pandemic at a time when training is even more critical to address the emerging shifts withing the agency. These important points must be taken into consideration with the recognition that reinforcing cohesion within the department, attracting new recruits, and retaining current policers officers will depend on how successfully the Honduras Government responds. While there are some likely positive outcomes of new procedures during the pandemic (i.e., virtual adaptations and leveraging technology), it will be critically important to address factors that could undermine public safety and trust in the police.

References

ReferencesACLED. (2020). Central America and COVID-19: The pandemic’s impact on gang violence. https://acleddata.com/2020/05/29/central-america-and-covid-19-the-pandemics-impact-on-gang-violence/

Amadsun, S. (2020). COVID-19 palaver: Ending rights violations of vulnerable groups in Africa. World Development, 134,1-5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2020.105054

Asmann, P., & Jones, K. (2021). InSight Crime’s 2020 homicide round-up. InSight Crime. https://insightcrime.org/news/analysis/2020-homicide-round-up/

Boserup, B., McKenney, M., & Elkbuli, A. (2020). Alarming trends in US domestic violence during the COVID-19 pandemic. American Journal of Emergency Medicine, 38(12), 2753-2755. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajem.2020.04.077

Bottoms, A., & Tankebe, J. (2012). Beyond procedural justice: A dialogic approach to legitimacy in criminal justice. Jou M. (2020). The immediate impact of COVID-19 on law enforcement in the United States. American Journal of Criminal Justice, 45, 690-701. https://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/jclc/vol102/iss1/4/

Jones, D. J. (2020). The potential impacts of pandemic policing on police legitimacy: Planning past the COVID-19 crisis. Policing, 14(3), 579-586. https://doi.org/10.1093/police/paaa026

Krause, N. M, Freiling, I., Beets, B. & Brossard, D. (2020). Fact-checking as risk communication: The multi-layered risk of misinformation in times of COVID-19. Journal of Risk Research, 23(7-8), 1052-1059. https://doi.org/10.1080/13669877.2020.1756385

Laufs, J. & Waseem, Z. (2020). Policing in pandemics: A systematic review and best practices for police response to COVID-19. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 51, 1-17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2020.101812

Liberman, A. M., Best, S. R., Metzler, T. J., Fagan, J. A., Weiss, D. S. & Marmar, C. R. (2002). Routine occupational stress and psychological distress in police. Policing: An International Journal of Police Strategies & Management, 25(2), 421-439. https://doi.org/10.1108/13639510210429446

Luna, A. M., Brito, C. S., & Sanberg, E. A. (2007). Police planning for an influenza pandemic: case studies and recommendations from the field. Police Executive Research Forum. https://www.publicsafety.gc.ca/lbrr/archives/cnmcs-plcng/cn89173109-eng.pdf

Mazerolle, L., Bennett, S., Davis, J., Sargeant, E., & Manning, M. (2013). Procedural justice and police legitimacy: A systematic review of the research evidence. Journal of Experimental Criminology, 9(3), 245-274. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11292-013-9175-2

Montalvo, D. (2019). Resultados preliminares 2019: Barómetro de las Américas en Honduras. Latin America Public Opinion Project, Vanderbilt University. www.vanderbilt.edu/lapop/honduras/AB2018-19_Honduras_RRR_W_09.25.19.pdf

Morfini, N. (2020, April 29). Coronavirus and narcotics: Can drug cartels survive COVID-19? Al Jazeera. https://www.aljazeera.com/opinions/2020/4/29/coronavirus-and-narcotics-can-drug-cartels-survive-covid-19/

Ovalle, R. (2020). Monitoring and response to violence against women and children during the COVID-19 pandemic in Guatemala, Special Monthly Report No. 4, August 2020 [Unpublished report prepared for the U.S. Agency for International Development]. USAID Community Roots Project. Available by request from the authors.

PERF. (2020). The impact of COVID-19 on police recruitment and hiring practices. PERF Daily Critical Issues Report, June 12, 2020. Police Executive Research Forum. https://www.policeforum.org/covidjune12

Shirzad, H., Abbasi Farajzadeh, M., Hosseini Zijoud, S. R., & Farnoosh, G. (2020). The role of military and police forces in crisis management due to the COVID-19 outbreak in Iran and the world. Journal of Police Medicine, 9(2), 63-70. http://jpmed.ir/article-1-887-en.html

Stogner, J., Miller B. L., & McLean, K. (2020). Police stress, mental health, and resiliency during the COVID-19 pandemic. American Journal of Criminal Justice, 45, 718-730. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12103-020-09548-y

Terrill, W., Paoline, E. A., & Gau, J. M. (2016). Three pillars of police legitimacy: Procedural justice, use of force, and occupational culture. In: M. Deflem (ed.), The Politics of Policing: Between Force and Legitimacy. 59-76. Emerald Group Publishing.

Ungureanu, P. & Bertolotti, F. (2020). Backing up emergency teams in healthcare and law enforcement organizations: Strategies to socialize newcomers in the time of COVID-19. Journal of Risk Research, 23(7-8), 888-901. https://doi.org/10.1080/13669877.2020.1765002

UNDP/USAID. (2020, August). Analysis of the state of the violence and citizen security: First semester 2020 (1s-2020). United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) and the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). https://www.hn.undp.org/content/honduras/es/home/presscenter/articles/AnalisisViolencia2020.html

UNHCR. (2020, May 15). Central America’s displacement crisis aggravated by COVID-19. United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. https://www.unhcr.org/news/briefing/2020/5/5ebe47394/central-americas-displacement-crisis-aggravated-covid-19.html

UNICEF Help Desk. (2018). Gender-based violence in emergencies: Emergency response to public health outbreaks. UNICEF. http://www.sddirect.org.uk/media/1617/health-responses-and-gbv-short-query-v2.pdf

UNODC. (2019). UNODC 2019 Global Study on Homicide. United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. https://www.unodc.org/unodc/en/data-and-analysis/global-study-on-homicide.html

UTECI. (2020). Caracterización de muertes violentas del 16 de marzo al 15 de septiembre, años 2019-2020: Datos preliminares. Mesa Técnica de Muertes Violentas; Secretaría de Seguridad/Policía Nacional (DPPOMC/SEPOL), Subsecretaría en Asuntos Interinstitucionales, Unidad Técnica de Coordinación Interinstitucional (UTECI).

Violanti, J. M., Charles, L. E., McCanlies, E., Hartley, T. A., Baughman, P., Andrew, M. E., et al. (2017). Police stressors and health: A state-of-the-art review. Policing, 40(4), 642-656. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30846905/

Worldometer.info. (2021, August 18). WORLD / COUNTRIES / HONDURAS. Worldometer. https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/country/honduras/