Ethical and methodological issues in the study of dating violence among young Mexicans: A systematic review

Aspectos éticos y metodológicos en el estudio de la violencia en el noviazgo entre jóvenes mexicanos: una revisión sistemática

Aspectos éticos e metodológicos no estudo da violência no namoro entre jovens mexicanos: uma revisão sistemática

José Luis Rojas-Solísa* | Saúl Hernández-Cruzb | Esmeralda Morales-Francoc | María de la Paz Toldos Romerod

a https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6339-4607 Benemérita Universidad Autónoma de Puebla, Puebla, México

b https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6599-2720 Benemérita Universidad Autónoma de Puebla, Puebla, México

c https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4538-1973 Benemérita Universidad Autónoma de Puebla, Puebla, México

d https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6068-7065 Tecnológico de Monterrey, México

ABSTRACT

Violence in young couples is a serious problem that has drawn the attention of the international scientific community, which led to an increase in the number of studies carried out on the subject in Mexico. For this reason, this systematic review synthesizes the ethical and methodological aspects of studies on dating violence among Mexican youths published in the last two decades. In line with a Prisma protocol, a search was carried out in the Clarivate, Ebsco, Scielo and Scopus databases. Of the total 639 initial references, a total of 12 articles that met the inclusion criteria were analysed through a purification process that was divided into four phases (publication between 2000 and 2019, empirical articles, English or Spanish language, Mexican sample, age group between 17 and 35, and heterosexual couples). Among the main results, the predominance of the quantitative approach, non-experimental and cross-sectional designs, as well as the inclusion of non-probabilistic and non-representative samples were highlighted. Likewise, numerous inconsistencies were found in ethical aspects of psychological research. The results and the methodological implications are discussed, prioritizing the urgency for future studies to correct the mandatory ethical aspects in order to avoid bad practices or risks for the participants.

Keywords: violence, dating, university students, young people, systematic review

Resumen

La violencia en parejas de jóvenes es un problema grave que ha llamado la atención de la comunidad científica internacional, lo cual supuso un aumento de los estudios realizados sobre la materia en México. Por esta razón, esta revisión sistemática sintetiza los aspectos éticos y metodológicos

de los estudios sobre violencia en el noviazgo de jóvenes mexicanos publicados en las últimas dos décadas. De acuerdo con un protocolo Prisma se realizó una búsqueda en las bases de datos Clarivate,

Ebsco, Scielo y Scopus. Del total de 639 referencias iniciales, se analizaron, mediante un proceso de

depuración dividida en cuatro fases, un total de 12 artículos que cumplieron con los criterios

de inclusión (publicación entre el 2000 y el 2019, artículos empíricos, idioma inglés o español, muestra mexicana, franja de edad entre los 17 y los 35, y muestra con parejas heterosexuales). Entre los principales resultados se destacó la predominancia del enfoque cuantitativo, diseños no experimentales y transversales, así como la inclusión de muestras no probabilísticas y no representativas. Asimismo, se hallaron numerosas inconsistencias en aspectos éticos sobre investigación psicológica. Se discuten los resultados y las implicaciones metodológicas, priorizando la urgencia de que futuros estudios subsanen los aspectos éticos obligatorios a fin de evitar malas prácticas o riesgos para los participantes.

Palabras clave: violencia, noviazgo, universitarios, jóvenes, revisión sistemática

RESUMO

A violência em casais de jovens é um problema sério que tem chamado a atenção da comunidade científica internacional, o que supôs um aumento dos estudos realizados sobre a matéria no México. Por este motivo, esta revisão sistemática sintetiza os aspectos éticos e metodológicos dos estudos sobre violência no namoro de jovens mexicanos publicados nas últimas duas décadas. De acordo a um

protocolo Prisma, realizou-se uma busca nas bases de dados Clarivate, Ebsco, Scielo e Scopus. De um total de 639 referências iniciais, foram analisados, através de um processo de depuração dividida em quatro fases, um total de 12 artigos que cumpriram os critérios de inclusão (publicação entre 2000 e 2019, artigos empíricos, idioma inglês ou espanhol, amostra mexicana, faixa etária entre os 17 e os 35 anos, e amostra com casais heterossexuais). Entre os principais resultados, destacou-se a

predominância da abordagem quantitativa, desenhos não experimentais e transversais, bem como

a inclusão de amostras não probabilísticas e não representativas. Da mesma forma, foram identificadas numerosas inconsistências em aspectos éticos sobre pesquisa psicológica. Se discutem os resultados e as implicações metodológicas, priorizando a urgência de que futuros estudos corrijam os aspectos éticos obrigatórios com o objetivo de evitar práticas indevidas ou riscos para os participantes.

Palavras-chave: violência, namoro, universitários, jovens, revisão sistemática

In the university context, it is possible to identify a great interaction between adolescents and adults due to the high percentage of both 17-year-olds entering university (De Garay, 2003) and those over 30 (Guzmán & Serrano,

2011). These are two vital stages of the life cycle that contextualize life-long relationships (Papalia, Sterns,

Feldman & Camp, 2009) and so they play a significant role in the development of well-being during adolescence and emerging adulthood (Gómez-López, Viejo & Ortega-Ruiz, 2019). For adolescents, these relationships facilitate learning experiences that promote relational patterns, as well as relationship building and nonviolent relationships. On the other hand, in early adulthood, romantic relationships, with individuals often dating, become a context where individuals encounter different experiences with their partners, such as the initiation or increase of sexual activity and independence (Corzo & Sarai, 2018). However, in both stages of the life cycle, situations of dating violence can also occur with greater frequency and severity.

Dating violence in university students

Aggressive behavior is a basic and primary behavior in the activity of living beings that is present in the entire animal kingdom. It is a multidimensional phenomenon in which a large number of factors are involved. For its part, aggression can occur in human and animal contexts and refers to an effective, intentional act with aversive consequences that presents an expressive variety; among the most frequent are those of a physical and verbal nature (Carrasco & González, 2006).

Furthermore, violence has been defined, in general terms, as the deliberate use of physical force or power against oneself, another person, a group, or a community (Espín, Valladares, Abad, Presno & Gener, 2008), although it can also be understood as a social process that includes various forms of aggression and is characterized by having a multiplying and expansive effect that not only affects

victims, but also society at large. It is a behavior that tends to be intentional and harmful to the other person and can be active or passive, that is, by action or omission. Likewise, it is multifactorial in origin and highlights biological or

hereditary facts, as well as the combination of the environment in which it develops. Furthermore, the consequences of any type of violence exerted can be irreversible in the affected person and tend to trigger more violent acts

towards another person or group (Martínez, 2016).

In this context, the relationship between aggression,

aggressiveness and violence can be confusing, therefore it is necessary to remember that violence is a behavior of gratuitous and cruel aggressiveness, while aggressiveness is an adaptive emotional behavior or response when activating biological mechanisms of defense against environmental hazards; however, violence is not justified by natural aggressiveness (Arias, 2013).

However, dating violence (DV) is a widespread problem in adolescence (Gracia-Leiva, Puente-Martínez, Ubillos-Landa & Páez-Rovira, 2019), although it can also relate to young adults and present a reciprocal pattern between men and women (Rubio-Garay, Carrasco & García-Rodríguez, 2019).

The study on this phenomenon is nothing new, with Kanin (1957) being one of the first authors addressing this

phenomenon. However, it was Makepeace (1981), with

his research in the United States, who would regain interest in the study of this problem. Currently, DV is understood as any attempt to control or dominate a person, either physically, sexually, or psychologically, and generate some type of damage to them (Rey-Anacona, 2009). Its existence has been associated with negative consequences in young people such as poor academic performance,

anxiety-depressive symptoms, drug use, low self-esteem, alcohol consumption, or the beginning of sexual relations at an early age (Pazos, Oliva & Hernando, 2014).

In addition to these factors, this type of violence can be invisible due to the fact that dating relationships are

considered trivial, temporary, or because third parties

understand that what happens within them must be kept in the couple’s private and intimate space, impeding the possibility of third party intervention (Páramo & Arrigoni,

2018), even if justified by the members of the dyad as part of a game or joke context (Muñoz-Rivas, Gómez, O’Leary & Lozano, 2007). All of this could have smoothed out the appearance of new types of intimate partner

violence, such as cyber violence, which is a type of

virtual violence considered to be a relatively new and growing phenomenon developed alongside the use of

information technology and communication, which consists of behaviors that seek to control, humiliate, hurt, expose, ridicule, or isolate an individual through the use of electronic or digital means (Romo-Tobón, Vázquez-Sánchez, Rojas-Solís & Alvídrez, 2020).

The alarming nature of the DV lies in the fact that it

occurs at the beginning of the relationship and can

increase in both frequency and intensity (Trujano, Nava, Tejeda & Gutiérrez, 2006). In this way, it has been suggested that the younger the age at which sexual intercourse begins, the higher the rate of physical violence suffered or, on the other hand, that the older and longer the relationship, the higher the rate of physical violence suffered, mainly in women. Added to this, young people could consider jealousy to be a sign of love and appreciation, thus making it difficult to recognize behaviors of control and isolation in the couple (Montilla, Romero, Martín & Pazos, 2017). In the same order of ideas, the empirical evidence indicates that there are no marked differences by sex in the prevalence of violence, mainly in that of a physical and psychological nature, although there is a difference in sexual nature, which seems to be carried out more frequently by men (Rey-Anacona, 2013). However, significant differences have been found in verbal violence, since it presents higher levels of incidence than physical

violence and it has been suggested that it is more frequently committed by women (Muñoz & Benítez, 2017), while other studies indicate that the most frequent violence in university students is psychological, specifically through control actions carried out by men (Carranza & Galicia, 2020), perhaps because men tend to have a greater acceptance of various types of violence compared to women (Muñoz- Ponce, Espinobarros-Nava, Romero Méndez, & Rojas-Solís, 2020). Despite this, it is important to clarify that the most serious or pernicious effects are usually directed towards women (Horcajo, Graña &

Rodríguez, 2019; Straus & Ramirez, 2007).

On the other hand, in Mexican society such types of

violence have been highlighted as factors associated with gender stereotypes because they promote a masculine image represented by strength, aggressiveness, initiative, and power, which characterize violent behaviors, while the female image in most cases is associated with passive and expressive roles, typical of a victim figure (Nava-Reyes, Rojas-Solís, Toldos & Morales, 2018). Similarly, specifically

in the young population, it is possible to highlight the sociocultural changes that have occurred in recent years that have facilitated the emergence of a two-way perspective on violence, assuming that the victim, whether male or female, may be able to actively carry out violent actions considering, in turn, that the victimizer could assume a passive role (Rojas-Solís, 2011).

This possible bidirectionality, normalization, and acceptance of violent behaviors as a valid means to resolve conflicts, as well as the distinction between the types of violence, exercised or suffered by men and women, should be considered when analyzing the phenomenon in adolescent couples and young adults (Alegría & Rodríguez, 2015; Cancino-Padilla, Romero-Méndez & Rojas-Solís, 2020). Thus, and without detriment to the possible exchange of roles between the aggressor and the victim on the part of women and men, it should be remembered that this bidirectionality does not necessarily imply the same gravity

in the consequences of violence (Straus & Ramirez, 2007); additionally, it is essential to consider the context,

especially in gender issues (Delgado-Álvarez, 2020;

Ferrer-Pérez & Bosch-Fiol, 2019), in order to understand violent behavior.

Therefore, the detection and the study of this phenomenon has captured the attention of numerous investigations, especially for its prevention (Trabold, McMahon, Alsobrooks, Whitney & Mittal, 2020), since it is especially alarming that at these ages the presence of these behaviors seems to be frequent (Rojas-Solís, 2013a), and that many adolescents consider them to be normal practices for conflict resolution or inherent in their own relationship (Rubio-Garay, Carrasco, Amor & López-González, 2015). Regardless, there remain few valid and reliable

instruments that allow researchers to diagnose and measure the phenomenon (Benítez & Muñoz, 2014), at least in Latin American contexts, thus becoming a limitation for the increase in the theoretical and empirical corpus

of the region. There is also a lack of papers on the treatment of this problem, which seems to suggest the scarcity of programs specifically aimed at intervening individually or in groups in cases of DV (Martínez & Rey-Anacona, 2014). Hence there is a need to carry out systematic reviews to reveal the empirical research corpus generated

(Rubio-Garay, López-González, Carrasco & Amor, 2017). In this sense, it should be noticed that there are numerous

systematic reviews on DV in the international context that focus on different aspects, such as factors associated with DV (Gracia-Leiva et al., 2019), prevalence

(Rubio-Garay et al., 2017), the instruments (López-Cepero,

Rodríguez-Franco & Rodríguez-Díaz, 2015; Yanez-Peñúñuri,

Hidalgo-Rasmussen & Chávez-Flores, 2019a), the interventions (Alegría & Rodríguez, 2015; Yanez-Peñúñuri, Martínez-Gómez & Rey-Anacona, 2019b), or the emergence of other types of violence (Rodríguez-Domínguez, Pérez-Moreno & Durán, 2020). Currently, however, up to the time of carrying out this study, narrative reviews can only be found within the Mexican context on DV among adolescents (Rojas-Solís, 2013a) and Mexican university students (Rojas-Solís, 2013b).

Consequently, the question that will guide this research is: what are the main characteristics of the studies

carried out between the years 2000 and 2019 on DV among young Mexican university students in terms of approach, design, scope, cut (study), sample, procedure, compliance with minimum ethical requirements, as well as the instruments used to evaluate the DV? To answer this query, Urrutia and Bonfill (2010) suggest explicitly asking the main questions to be answered in relation to the participants, interventions, comparisons, results, and study design, but this review is directed only toward the participant analysis and research design, so it was not possible

to fully implement this tool. The subsequent intention is to synthesize the existing evidence regarding a health issue in order to generate new hypotheses, lines of

research, as well as to propose more appropriate working methods for future research (Manchado et al., 2009) or in the prevention of violence in young university students.

Methodology

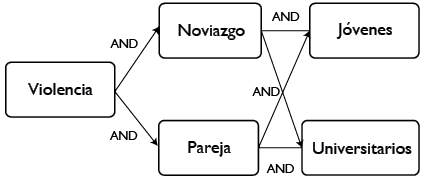

A systematic exploratory review was carried out following the suggestions of the PRISMA model (Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff, Altman & PRISMA Group, 2009). Combinations were made between the selected keywords in English (dating, violence, partner, university students, young) (see

Figure 1) and Spanish (violence, couples, young people, university students, dating) (see Figure 2) in order to arm search strings with the Boolean operator AND, and enter them into the selected databases.

Figure 1. English search string

Figure 2. Spanish search string

Procedure

The search in the Clarivate, EBSCO, Scielo, and SCOPUS databases was performed between June and July 2019 using the advanced search function in order to enter the aforementioned search strings with the default option (select a field) applying the following filters: (1) publication date from 2000 to 2019; (2) full text; and (3) results with open access. The inclusion and exclusion criteria were as follows:

• Inclusion criteria. (1) Articles published between 2000 and 2019; (2) empirical articles; (3) English and/or Spanish language; (4) articles dealing with DV; (5) Mexican sample; (6) age group from 17 to 35 years; and (7) a sample with heterosexual couples.

• Exclusion criteria: (1) Articles not included in the 2000-2019 interval; (2) review articles, contributions to

conferences, gray literature; (3) articles not written in Spanish and/or English; (4) non-Mexican sample; (5)

a sample that does not comply with the age group; and (6)

samples with non-heterosexual couples (LGBT+ community).

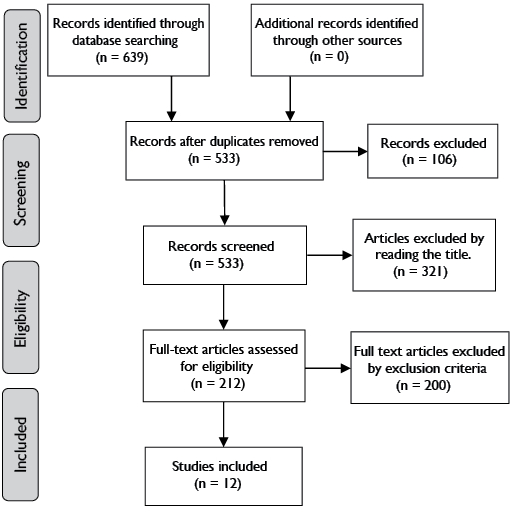

The recovery and filtering of articles was divided into four phases where articles were discarded according to the specified inclusion and exclusion criteria (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. PRISMA flow diagram (Moher et al., 2009).

• Phase 1. In this phase, the articles were collected through the previously mentioned search strings. These articles were downloaded and their data was added to an Excel table with the following content for analysis: (a) article name, (b) author or authors, (c) year of publication, (d) country, (e) language, (f) journal, and (g) type of publication.

• Phase 2. For this stage, a first exclusion filter was applied to the retrieved papers, namely papers that: (a) included a non-Mexican sample, (b) were not about DV, or (c) did not investigate young or university students. Likewise, those articles that were potentially relevant candidates for a partial review were included.

• Phase 3. Four filter questions were included in this phase to delimit the papers only to those that were included in the final review. The filters were: (1) is the sample with a Mexican population? (2) Is the sample aged from 17 to 35 years old? (3) Does the sample only include heterosexual couples? Finally, (4) is it an empirical article? The inclusion criterion was that it fulfilled the requirements in the four filter questions in order to be a candidate for a complete review in the next stage.

• Phase 4. The final choice was made up of twelve articles, and the data obtained for their analysis was the following: keywords, focus, design, scope, cut, sample (size, sex, selection, type, age), and instrument (name, authorship, evaluation focus).

Ethical aspects

This work deals with a systematic review and was a research study without risk because retrospective research papers were analyzed. Added to this, this work considers what is stated in the Declaration of Helsinki, the APA Code of Ethics (2017), and the Mexican Society of Psychology (2010). Therefore, the copyright of the corresponding articles was taken into account when making the respective citations and references of the sources consulted.

Data analysis

Microsoft © Excel 2018 was used to prepare the database that included the various phases that hosted and categorized the identified and selected studies. Four main characteristics were extracted from these materials: descriptive, methodological, sampling, and procedural.

Results

In the first phase, a total of 639 articles were obtained with the four search chains, reaching a total of 12 articles for the final review, which went through a filtering process.

Table 1 shows a summary of the results found through the systematic review of the included studies. First, we find the identification data of the articles that were included in the systematic review for analysis; Saldívar and Lazarevich stand out in this context with a total of three and two articles, respectively. Regarding the country of publication, Mexico is found with five articles, followed by the United States with three. In terms of the language of publication, most were written in Spanish (ten articles), with the remaining two written in English. Finally, regarding the keywords, the great diversity of keywords included in the studies on DV stands out, including: sexual coercion, university students, gender, Mexico, dating, violence, and DV.

Table 2 shows the focus and design characteristics of the articles. They are mostly quantitative, non-experimental, exploratory, descriptive, and cross-sectional studies.

On the other hand, Table 3 illustrates the characteristics corresponding to the samples of each study, in which the selection was of a non-probabilistic type. Significant variations were found in the size and distribution of male and female participants, with the number of women being greater in most of the studies.

The procedure used in the study is also presented, which includes the ethical aspects centering around three main areas: (1) the type of collection (whether it was personal

or virtual); most of the investigations collected data off-line¸ while only three used online resources; (2) ethical aspects, in which in several investigations areas of opportunity were pointed out (in this sense, the confidentiality

of the data was ensured in all the studies analyzed, however, the anonymity and voluntary participation were conditions that were not mentioned by some authors, including elements like the approval of studies by an Ethics Committee or the allusion to a legal or ethical framework for research); and (3) the choice and justification of the data analyses, where most of the investigations indicated the data analysis plan, while a few justified the choice of the statistical analyses carried out.

Finally, Table 4 reveals the corresponding characteristics of the instruments of each article, in which it is necessary to point out the diversity of dimensions of violence that each one evaluates, since they do not focus on a single type of violence, thus highlighting sexual coercion, DV,

and types of violence, among others, as well as other independent variables of each study topic.

In relation to the evaluation of the phenomenon, most of the instruments were ad hoc, that is, designed according to the characteristics and the objectives of the research. Likewise, it is important to highlight the use of scales such as CUVINO and CADRI, which have reliability and validity for the Mexican population and with specific use in samples of young people.

Discussion

The present systematic review aimed to answer the following question: what are the main characteristics of the studies carried out between the years 2000 and 2019 on DV among young Mexican university students in terms of approach, design, scope, cut (study), sample, procedure, compliance with minimum ethical requirements, as well

as the instruments used to evaluate the DV? A discussion of the findings is presented below.

Regarding the approach, it should be noted that the majority of studies opted for a quantitative approach, which allows the evaluation of, among other issues, the frequency with which the phenomenon occurs, but not aspects such as the experience, meanings, or contexts of the violence. Likewise, the designs were non-experimental, cross-sectional, and with scopes, mostly exploratory or descriptive, which does not allow the extraction of causal relationships between the variables, as well as a knowledge

of the dynamics of violence over time.

However, the samples were non representative and

selected in a non-probabilistic manner, thus hindering the generalization of results. Additionally, a large number of the studies indicate women as the main participants, perhaps because most of these investigations focus on

violence towards women, and, therefore, the evaluation of the risk of victimization for men turns out to be

limited, thus obviating the possibility of said phenomenon (Rojas-Solís, Guzmán-Pimentel, Jiménez-Castro, Martínez-Ruiz & Flores-Hernández, 2019).

However, regarding the procedure, most of the investigations still collected data off-line¸ however, some studies used online resources, which in other contexts is becoming general and would imply other ethical requirements.

In this sense, the ethical aspects were crucial points in which in several investigations areas of opportunity were indicated. Likewise, the confidentiality of the data was ensured in all the studies analyzed; however, the anonymity and voluntary participation of subjects were conditions that were not mentioned by the authors. This is of the utmost importance considering that the principle of

respect for the participants’ autonomy, meaning they can withdraw from the study at any time by requesting the letter of informed consent, beyond being a legal requirement constitutes a commitment between the participant and the researcher to safeguard the voluntariness, the

anonymity, and the privacy of the participants, and

the information obtained from them (Miranda-Novales &

Villasís-Keever, 2019).

However, in some cases informed consent was not included in the studies, which indicates a great deficiency due to the fact that the information on the objectives and the nature of the research, the procedures to be carried out, and the obtaining of free consent to participate had to be issued, in addition to the exposition of the possible risks of the study, all of this in accordance with the

General Law of Health in Matters of Health Research

(Miranda-Novales & Villasís-Keever, 2019), as well as

ethical regulations such as the Code of Ethics of the APA (2017), the Mexican Society of Psychology (2010), or the declaration of Helsinki (AMM, 2000), thus avoiding the notion that the participants are only a useful object of knowledge (Palencia & Ben, 2013).

In most investigations, approval of the study by an ethics committee was absent. This is a highly important element, since it would be more than desirable for an interdisciplinary and plural body to evaluate the research project in order to promote higher standards of ethics in health research (Rubio-Rincón, Molina-Montoya & Jurado-

Medina, 2019). In this same sense, it would be pertinent to explain the legal framework that is supporting the

bioethical values and the principles that research on human beings demands (Mazzanti, 2011). Along these lines, the importance of promoting and strengthening ethics in psychological praxis from university classrooms has been pointed out, so that possible harm is avoided to those who participate in the investigations (Chávez, Santa Cruz & Grimaldo, 2014).

Finally, the offer of subsequent psychological support should be considered as part of the ethical research

protocol to guarantee the well-being of the participants in case they need it, even in order to reduce the risk of

unintended consequences, thus complying with the

principle of beneficence (non-maleficence), by which

the researcher must ensure that the risks are identified and, if they occur, would be addressed immediately (Miranda-

Novales & Villasís-Keever, 2019).

With reference to data analysis, in some studies parametric

techniques were performed despite the size and the

disproportion of the samples, as well as the expected violation of the assumption of normality in a variable such as violence; added to this, information on the reliability and the validity of the tests separately in men and women, or as a whole group, was not available in most of the articles, so it was decided not to include these data in the table of analysis. In this sense, caution would be required in the extraction of inferences from the aforementioned studies.

On the other hand, most of the instruments were ad hoc, that is, designed according to the characteristics and the objectives of the research. These types of questionnaires or scales entail, among other things, questions about their reliability and validity, without forgetting that they are rarely used again, thus hindering the replication of

findings and, therefore, the strengthening of psychometric

resources around evaluation of the phenomenon.

However, some of the instruments implemented did not focus on evaluating the violence suffered or committed, but rather related to aspects such as the tactics, attitudes, perception, myths of rape and sexual coercion, or omit other types of violence by mainly focusing on sexual violence. This is not surprising if one considers an international

research context where it seems that there are still few instruments that specifically and comprehensively evaluate violence against young people, considering the physical, sexual, control, and psycho-emotional dimensions, both in the violence exerted and received (García-Carpintero, Rodríguez-Santero & Porcel-Gálvez, 2018). Therefore, it is necessary to continue updating the knowledge about the properties of the instruments used in the region to measure DV (Yanez-Peñúñuri et al., 2019a).

An adjacent finding was the large number of keywords included in the studies on DV, which denotes a wide variety of concepts associated with this phenomenon (Jennings et al., 2017), as well as the different types of violence, which complicates the conducting of a systematic review due to the large number of descriptors that would have to be used to optimize the search strings of the relevant papers. In this regard, Rubio-Garay et al. (2015) have suggested that this could be related to the great heterogeneity of conceptual definitions on DV, the use of different instruments for its measurement, and, in addition to this, its application to a different type of population and geographic area than the instrument was designed for.

Among the limitations of this research work, the

selection of databases stands out, which, despite being of quality, numbered only four; perhaps for this reason, a small number of articles were obtained with Mexican samples. Likewise, it is necessary to recognize the rigidity of the inclusion criteria, specifically when dealing with samples with Mexican university students. However, this study presents some strengths such as, for example, the systematization of empirical research with Mexican

samples from the last 20 years, which is focused on the methodological and instrumental aspects that allow a vision of the strengthening of the empirical evidence accumulated in Mexico, as well as its opportunity areas.

The importance of exploratory reviews is based on the panorama that they give to make theoretical or methodological decisions, such as, for example, the development of more precise hypotheses based on the results obtained, thus generating future questions and lines of research (Manchado et al., 2009).

In this sense, one of the most important implications of this work derives from the conceptual scope, because the variability of the keywords related to the DV, beyond

logomachy, suggests the importance of a conceptual and terminological consensus that would allow the unification of theoretical criteria and, with it, the ease of replication of

results. This is the study of a critical phenomenon,

considering the fundamental role that romantic relationships play in the well-being of emerging adolescents and adults (Gómez-López, Viejo & Ortega-Ruiz, 2019).

Regarding the empirical implications for future studies on DV, one could consider the individual aspects that are frequently forgotten, mainly the biological (Soldino, Romero-Martínez, Ángel & Moya-Albiol, 2015), psychopathological (Clements, Clauss, Casanave & Laajala, 2018) or criminogenic (Arias, 2013) correlates of the couple. Likewise, an interactional and contextual perspective should also be included in such a way that it allows

researchers to understand the dynamics within the couple, the motivations or the reasons for exercising violence, and if it is carried out bidirectionally based on a defense or against attack against a received aggression, all for the sake of “avoiding a simple explanation for a complex

phenomenon” (Echeburúa, 2019, p. 79).

Among the methodological implications, there is a need for more research with mixed and qualitative approaches, the use of experimental designs with longitudinal

ranges, the inclusion of probabilistic and representative samples of the population, as well as the application of validated and reliable instruments adapted to Mexican samples. This will facilitate greater knowledge of the

phenomenon in order to identify, among other issues, the meaning of violence by young people, the modeling of

victim and aggressor profiles, the evolution of the phenomenon individually and in pairs over time, explanatory factors through experimental designs, as well as the necessary inclusion of couples in the study of a phenomenon that is by nature dyadic. All this for the design of effective prevention and intervention actions based on empirical evidence.

Regarding the procedure, the advent of more online studies is expected, which will pose new methodological and, above all, ethical challenges, in light of the results obtained. In this aspect, it is also necessary to solve the great problem that represents the absence of good practices in psychological research in the analyzed studies, an urgent but not recent challenge, since it has already been pointed out in other investigations (Baena, Fuster, Carbonell & Oberst, 2010).

Similarly, the ethical implications highlight the relevance of correcting, as quickly as possible, the minimum considerations of respect for the freedom, the autonomy, the privacy, and the well-being of the participants, failures that, although not exclusive to this type of study (Martín-

Arribas, Rodríguez-Lozano & Arias-Díaz, 2012), constitute a great opportunity area. Now, although until recently the general need for approval has been imposed on projects of this nature, it is increasingly desirable to have the

review and the approval of an ethics committee for the better development of research practices in psychology

(Chávez et al., 2014). Added to this, it is necessary to

remember the desirable provision of psychological

support following the collaboration, if required, in order to preserve the integrity and the well-being of the participants. Carrying out research that includes a large part of these elements would lead to valid results that support an ethical advance in science (Richaud, 2007).

Future systematic reviews could increase the number of databases in order to obtain a broader overview of the study of DV in Mexico, in the same way that future empirical

research could consider the diversity of relationships that exist in addition to courtship, as well as its different

conceptualizations, in addition to the analysis of other variables and methodological issues such as diversifying the type of population or the use of validated instruments to evaluate and diagnose the phenomenon.

References

Alegría, M., & Rodríguez, A. (2015). Violencia en el noviazgo: perpetración, victimización y violencia mutua. Una revisión. Actualidades en Psicología, 29(118), 57-72. https://doi.org/10.15517/ap.v29i118.16008

APA (American Psychological Association). (2017). Ethical principles of psychologists and code of conduct. https://www.apa.org/ethics/code/ethics-code-2017.pdf

Arias, W. L. (2013). Agresión y violencia en la adolescencia: la importancia de la familia. Avances en Psicología, 21(1), 23-34. https://doi.org/10.33539/avpsicol.2013.v21n1.303

AMM (Asociación Médica Mundial). (2000). Declaración de Helsinki de la AMM: principios éticos para las investigaciones médicas en seres humanos, quinta versión. https://www.wma.net/es/policies-post/declaracion-de-helsinki-de-la-amm-principios-eticos-para-las-investigaciones-medicas-en-seres-humanos/

Baena, A., Fuster, H., Carbonell, X., & Oberst, U. (2010). Retos metodológicos de la investigación psicológica a distancia. Revista de Psicologia, Ciències de l’Educació i de l’Esport, (26), 137-156.

Benítez, J. L., & Muñoz, J. F. (2014). Análisis factorial de las puntuaciones del CADRI en adolescentes universitarios españoles. Universitas Psychologica, 13(1), 1-19. https://doi.org/10.11144/Javeriana.UPSY13-1.afpc

Cancino-Padilla, D., Romero-Méndez, C. A., & Rojas-Solís, J. L. (2020). Exposición a la violencia, violencia filioparental y en el noviazgo de jóvenes mexicanos. Interacciones, 6(2). https://doi.org/10.24016/2020.v6n2.228

Carranza, R., & Galicia, I. X. (2020). Violencia de pareja en estudiantes universitarios. Un estudio comparativo entre carreras y semestres. Pedagogía Social, 35(9), 113-123. https://doi.org/10.7179/PSRI_2020.35.09

Carrasco, M., & González, M. J. (2006). Aspectos conceptuales de la agresión: definición y modelos explicativos. Acción Psicológica, 4(2), 7-38. https://doi.org/10.5944/ap.4.2.478

Carrasco-Lozano, M. E. (2018). El género de la violencia en las aulas universitarias, una realidad invisibilizada. El Cotidiano, 34(212), 87-96. https://issuu.com/elcotidiano/docs/cotidiano_212/88

Chávez, V. G., Santa Cruz, E. H., & Grimaldo, M. M. (2014). El consentimiento informado en las publicaciones latinoamericanas de psicología. Avances en Psicología Latinoamericana, 32(2), 345-359. https://doi.org/10.12804/apl32.2.2014.12

Clements, C., M., Clauss, K., Casanave, K., & Laajala, A. (2018). Aggression, psychopathology, and intimate partner violence perpetration: does gender matter? Journal of Aggression Maltreatment & Trauma, 27(8), 902-921. https://doi.org/10.1080/10926771.2017.1410750

Corzo, C., & Sarai, L. (2018). Antecedentes históricos de las relaciones amorosas en la adolescencia y los problemas psicológicos que se generan durante estas (capítulo uno). UAEH, 5(9). https://repository.uaeh.edu.mx/revistas/index.php/prepa3/article/view/2862

De Garay, A. (2003). El perfil de los estudiantes de nuevo ingreso de las universidades tecnológicas en México. El Cotidiano, 19(122), 75-85.

Delgado-Álvarez, C. (2020). La ceguera al género inducida por la ceguera a los estándares de medición. Comentario

a Ferrer-Pérez y Bosch-Fiol, 2019. Anuario de Psicología

Jurídica, 30, 93-96. https://doi.org/10.5093/apj2019a8

Echeburúa, E. (2019). Sobre el papel del género en la violencia de pareja contra la mujer. Comentario a Ferrer-Pérez y Bosch-Fiol, 2019. Anuario de Psicología Jurídica, 29, 77-79. https://doi.org/10.5093/apj2019a4

Espín, J. C., Valladares, A. M., Abad, J. C., Presno, C., & Gener, N. (2008). La violencia, un problema de salud. Revista Cubana de Medicina General Integral, 24(4), 1-6.

Espinobarros-Nava, F., Muñoz-Ponce, N. N., & Rojas-Solís, J. L. (2018). Co-ocurrencia de violencia en el noviazgo en una muestra de jóvenes mexicanos procedentes de zona rural. Summa Psicológica, 15(2), 154-161. https://doi.org/10.18774/448x.2018.15.394

Esquivel-Santoveña, E. E., Rodríguez-Hernández, R., Gutiérrez-Vega, M., Castillo-Viveros, N., & López-Orozco, F. (2019). Psychological aggression, attitudes about violence, violent socialization, and dominance in dating relationships. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 1-22. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260519842856

Ferrer-Pérez, V. A., & Bosch-Fiol, E. (2019). El género en el análisis de la violencia contra las mujeres en la pareja: de la “ceguera” de género a la investigación específica del mismo. Anuario de Psicología Jurídica, 29, 69-76. https://doi.org/10.5093/apj2019a3

Flores-Garrido, N., & Barreto-Ávila, M. (2018). Violencia en el noviazgo entre estudiantes de la Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. Un análisis mixto. Revista Iberoamericana de Educación Superior, 9(26), 42-63. https://doi.org/10.22201/iisue.20072872e.2018.26.290

García-Carpintero, M. Á., Rodríguez-Santero, J., & Porcel-Gálvez, A. M. (2018). Diseño y validación de la escala para la detección de violencia en el noviazgo en jóvenes en la Universidad de Sevilla. Gaceta Sanitaria, 32(2), 121-128. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gaceta.2017.09.006

Gómez-López, M., Viejo, C., & Ortega-Ruiz, R. (2019). Well-Being and romantic relationships: a systematic review in adolescence and emerging adulthood. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(13), 2-30. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16132415

Gracia-Leiva, M., Puente-Martínez, A., Ubillos-Landa, S., & Páez-Rovira, D. (2019). La violencia en el noviazgo (VN): una revisión de meta-análisis. Anales de Psicología, 35(2), 300-313. https://doi.org/10.6018/analesps.35.2.333101

Guzmán, C., & Serrano, O. V. (2011). Las puertas del ingreso a la educación superior: el caso del concurso de selección a la licenciatura de la UNAM. Revista de la Educación Superior, 40(157), 31-53.

Herrera, J. M., & Arena, C. A. (2010). Consumo de alcohol y violencia doméstica contra las mujeres: un estudio con estudiantes universitarias de México. Revista Latino-Americana de Enfermagem, 18, 557-564.

Horcajo, P. J., Graña, J. L., & Rodríguez, N. (2019). The relationship between trial data in judicial sentences and self-reported aggression in men convicted of violence against women. Psicothema, 31(2), 134-141. https://doi.org/10.7334/psicothema2018.253

Jennings, W. G., Okeem, C., Piquero, A. R., Seller, C. S., Theobald, D., & Farrington, D. P. (2017). Dating and intimate partner violence among young persons ages 15-30: evidence from a systematic review. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 33, 107-125. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2017.01.007

Kanin, E. J. (1957). Male aggression in dating-courting relations. American Journal of Sociology, 63, 197-204. https://doi.org/10.1086/222177

Lazarevich, I., Irigoyen-Camacho, M. E., Sokolova, A. V., & Delgadillo, H. J. (2013). Violencia en el noviazgo y salud mental en estudiantes universitarios mexicanos. Global Health Promotion, 20(3), 94-103. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F1757975913499032

Lazarevich, I., Irigoyen-Camacho, M. E., Velázquez-Alva, M. D., & Salinas-Ávila, J. (2017). Dating violence in Mexican college students: evaluation of an educational workshop. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 32(2), 183-204. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260515585539

López-Cepero, J., Rodríguez-Franco, L., & Rodríguez-Díaz, F. (2015). Evaluación de la violencia de pareja. Una revisión de instrumentos de evaluación conductual. Revista Iberoamericana de Diagnóstico y Evaluación e Avaliação Psicológica, 2(40), 37-50.

Makepeace, J. M. (1981). Courtship violence among college students. Family Relations, 30(1), 97-102.

Manchado, R., Tamames, S., López, M., Mohedano, L., D´Agostino, M., & Veiga, J. (2009). Revisiones sistemáticas

exploratorias. Medicina y Seguridad del Trabajo, 55(216), 12-19.

Martín-Arribas M., Rodríguez-Lozano, I., & Arias-Díaz, J. (2012). Revisión ética de proyectos. Experiencia de un comité de ética de la investigación. Revista Española de Cardiología, 65(6), 525-529. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.recesp.2011.12.017

Martínez, A. (2016). La violencia. Conceptualización y elementos para su estudio. Política y Cultura, (46), 7-31.

Martínez, J. A., & Rey-Anacona, C. A. (2014). Prevención de violencia en el noviazgo: una revisión de programas

publicados entre 1990 y 2012. Pensamiento Psicológico, 12(1), 117-132.

Mazzanti, M. Á. (2011). Declaración de Helsinki, principios y valores bioéticos en juego en la investigación médica con seres humanos. Revista Colombiana de Bioética, 6(1), 125-144.

Miranda-Novales, M. G., & Villasís-Keever, M. A. (2019). El protocolo de la investigación VIII. La ética de la investigación en seres humanos. Revista Alergía México, 66(1), 115-122. https://doi.org/10.29262/ram.v66i1.594

Moher D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., Altman D. G., & The Prisma Group. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The Prisma Statement. PLoS Medicine, 6(6), e1000097. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097

Montilla, M. D., Romero, C., Martín, A., & Pazos, M. (2017). Actitudes de los adolescentes acerca de la violencia en parejas jóvenes. Revista de Orientación Educacional, 31(59), 53-72.

Muñoz, J. F., & Benítez, J. L. (2017). Incidencia de la violencia en la pareja en una muestra de adolescentes universitarios

españoles. Revista Argentina de Clínica Psicológica, 26(2), 183-193.

Muñoz-Ponce, N. N., Espinobarros-Nava, F., Romero-Mendez, C. A., & Rojas-Solís, J. L. (2020). Sexismo, celos y aceptación de violencia en jóvenes universitarios mexicanos. Revista Katharsis, 1(29), 3-21. https://doi.org/10.25057/25005731.1284

Muñoz-Rivas, M. J., Gómez, J. L. G., O’Leary, K. D., & Lozano, P. G. (2007). Agresión física y psicológica en las relaciones de noviazgo en universitarios españoles. Psicothema, 19(1), 102–107.

Nava-Reyes, M. A., Rojas-Solís, J. L., Toldos, M. P., & Morales, L. A. (2018). Factores de género y violencia en el noviazgo de adolescentes mexicanos. Boletín Científico Sapiens Research, 8(1), 54-70. https://www.aacademica.org/dr.jose.luis.rojas.solis/36

Palencia, M. L., & Ben, V. P. (2013). Ética en la investigación psicológica: una mirada a los códigos de ética de Argentina, Brasil y Colombia. Revista de Psicología, 9(17), 53-65.

Papalia, D. E., Sterns, H. L., Feldman, R. D., & Camp, C. J. (2009). Desarrollo del adulto y vejez. McGraw-Hill.

Páramo, M. D., & Arrigoni, F. (2018). Violencia psicológica en la relación de noviazgo en estudiantes universitarios mendocinos (Argentina). Archivos de Medicina, 18(2), 324-338. https://doi.org/10.30554/archmed.18.2.2738.2018

Pazos, M., Oliva, A., & Hernando, Á. (2014). Violencia en relaciones de pareja de jóvenes y adolescentes. Revista Latinoamericana de Psicología, 46(3), 148-159. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0120-0534(14)70018-4

Peña-Cárdenas, F., Rojas-Solís, J. L., & García-Sánchez, P. V. (2018). Uso problemático de internet, cyber bullying y ciber-violencia de pareja en jóvenes universitarios. Diversitas, 14(2), 205-219. https://doi.org/10.15332/s1794-9998.2018.0014.01

Rey-Anacona, C.A. (2013). Prevalencia y tipos de maltrato en el noviazgo en adolescentes y adultos jóvenes. Terapia Psicológica, 31(2), 143-154. https://doi.org/10.4067/S0718-48082013000200001

Rey-Anacona, C. A. (2009). Maltrato de tipo físico, psicológico, emocional, sexual y económico en el noviazgo: un estudio exploratorio. Acta Colombiana de Psicología, 12(2), 27-36.

Richaud, M. C. (2007). La ética en la investigación psicológica. Enfoques, 19(1-2), 5-18.

Rodríguez, R., Riosvelasco, L., & Castillo, N. (2018). Violencia en el noviazgo, género y apoyo social en jóvenes universitarios.

Escritos de Psicología, 11(1), 1-9. https://doi.org/10.5231/psy.writ.2018.2203

Rodríguez-Domínguez, C., Pérez-Moreno, P. J., & Durán, M. (2020). Cyber dating violence: a review of its research methodology. Anales de Psicología, 36(2), 200-209. https://doi.org/10.6018/analesps.370451

Rojas-Solís, J. L. (2011). Transformaciones socioculturales y aspectos de género: algunas implicaciones para el estudio de violencia en pareja. Revista Electrónica de Psicología Iztacala-UNAM, 14(3), 252-272.

Rojas-Solís, J. L. (2013a). Violencia en el noviazgo de adolescentes mexicanos: una revisión. Revista Educación y Desarrollo, 27(1), 49-58.

Rojas-Solís, J. L. (2013b). Violencia en el noviazgo de universitarios en México: una revisión. Revista Internacional de Psicología, 12(2), 1-31.

Rojas-Solís, J. L., Guzmán-Pimentel, M., Jiménez-Castro, M. P., Martínez-Ruiz, L., & Flores-Hernández, B. G. (2019). La

violencia hacia los hombres en la pareja heterosexual: una revisión de revisiones. Ciencia y Sociedad, 44(1), 57-70. https://doi.org/10.22206/CYS.2019.V44I1.PP57-70

Romo-Tobón, R. J., Vázquez-Sánchez, V., Rojas-Solís, J. L., &

Alvídrez, J. (2020). Cyberbullying y ciberviolencia de

pareja en alumnado de una universidad privada mexicana.

Propósitos y Representaciones, 8(2). https://doi.org/10.20511/pyr2020.v8n2.303

Rubio-Garay, F., Carrasco, M. Á., Amor, P. A., & López-González, M. Á. (2015). Factores asociados a la violencia en el noviazgo entre adolescentes: una revisión crítica. Anuario de Psicología Jurídica, 25(1) 47-56.

Rubio-Garay, F., Carrasco, M. Á., & García-Rodríguez, B. (2019). Desconexión moral y violencia en las relaciones de noviazgo de adolescentes y jóvenes: un estudio exploratorio. Revista Argentina de Clínica Psicológica, 28(1), 22-31.

Rubio-Garay, F., López-González, M. Á., Carrasco, M. Á., & Amor, P. A. (2017). Prevalencia de la violencia en el noviazgo: una revisión sistemática. Papeles del Psicólogo, 38(2), 135-147. https://doi.org/10.23923/pap.psicol2017.2831

Rubio-Rincón, G., Molina-Montoya, N., & Jurado-Medina, S. (2019). Logros y retos del Comité de Ética de la Investigación de la Facultad de Ciencias de La Salud ULS, Bogotá D. C. Revista Colombiana de Bioética, 14(1), 1-10. https://doi.org/10.18270/rcb.v14i1.2435

Saldívar, G., & Romero, M. P. (2009). Reconocimiento y uso de tácticas de coerción sexual en hombres y mujeres en el contexto de relaciones heterosexuales. Un estudio en estudiantes universitarios. Salud Mental, 32(6), 487-494.

Saldívar, G., Jiménez, A., Gutiérrez, R., & Romero, M. (2015). La coerción sexual asociada con los mitos de violación y las actitudes sexuales en estudiantes universitarios. Salud Mental, 38(1), 27-32.

Saldívar, G., Ramos, L., & Romero, M. (2008). ¿Qué es la coerción sexual? Significado, tácticas e interpretación en jóvenes universitarios de la ciudad de México. Salud Mental, 31(1), 45-51.

Sociedad Mexicana de Psicología. (2010). Código ético del psicólogo. México, D.F.: Trillas.

Soldino, V., Romero-Martínez, Á., & Moya-Albiol, L. (2015). Violent and/or delinquent women: a vision from the biopsychosocial perspective. Annals of Psychology, 32(1), 279-287. https://doi.org/10.6018/analesps.32.1.182111

Straus, M., & Ramírez, I. L. (2007). Gender symmetry in prevalence, severity, and chronicity of physical aggression against dating partners by university students in Mexico and USA. Aggressive Behavior, 33(4), 281-290. https://doi.org/10.1002/ab.20199

Trabold, N., McMahon, J., Alsobrook, S., Whitney, S., & Mittal, M. (2020). A systematic review of intimate partner violence interventions: state of the field and implications for practitioners. Trauma, Violence y Abuse, 21(2), 311-325. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838018767934

Trujano, P., Nava, C., Tejeda, E., & Gutiérrez, S. (2006). Estudio confirmatorio acerca de la frecuencia y percepción de la violencia: El VIDOFyP como instrumento de evaluación y algunas reflexiones psicosociales. Psychosocial Intervention, 15(1), 95-110.

Urrútia, G., & Bonfill, X. (2010). Declaración PRISMA: una propuesta para mejorar la publicación de revisiones sistemáticas y metaanálisis. Medicina Clínica, 135(11), 507–511. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.medcli.2010.01.015

Yanez-Peñúñuri, L. Y., Hidalgo-Rasmussen, C. A., & Chávez-Flores, Y. V. (2019a). Revisión sistemática de instrumentos de violencia en el noviazgo en Iberoamérica y

evaluación de sus propiedades de medida. Ciencia y Salud

Colectiva, 24(6), 2249-2262. https://doi.org/10.1590/1413-81232018246.19612017

Yanez-Peñúñuri, L. Y., Martínez-Gómez, J. A., & Rey-Anacona, C. A. (2019b). Therapeutic intervention for victims and perpetrators of dating violence: a systematic review. Revista Iberoamericana de Psicología y Salud, 10(2), 107-121. https://doi.org/10.23923/j.rips.2019.02.029